In April of this year, a group of Toshiba researchers published a landmark article in Nature that may have escaped the attention of our readers. In the article, the engineers and physicists demonstrated how quantum communication could be established between different cities using existing optical network infrastructure. Until now, quantum messages could only be transmitted via special, expensive, and labor-intensive networks. In fact, the “quantum internet” existed primarily on university campuses.

This new research opens a new chapter in the history of quantum networks and is a significant step toward the widespread adoption of this technology. But what exactly is quantum communication? Why is it necessary, and how does it work? What are the main advantages of quantum networks over classical ones, which seem to have no shortcomings? Today, we tackle these questions about a potentially transformative technology, using the work of Toshiba researchers as a starting point for discussion.

What is cryptography, and why is it needed?

Cryptographic tools are an essential part of data protection systems; no services can operate without them, from payment systems and email to classified military or government systems. Most of these cryptographic systems rely on asymmetric cryptography algorithms.

In symmetric cryptography, a single secret key is used both to encrypt and decrypt messages. However, to use this method, a secure channel is required to transmit the key; it cannot be sent over the same channel as the encrypted message.

Asymmetric cryptography overcomes this challenge by introducing a pair of keys – a public and a private one – instead of relying on a single shared secret. The public key is used to encrypt messages, while only the private key can unlock them. This means users can freely share their public keys and still communicate securely, since only their private keys can decrypt incoming messages.

Public-key cryptography is based on one-way functions – functions that are easy to compute for any given input but computationally difficult to invert. For example, multiplying two large numbers is straightforward, whereas factoring the product to recover the original numbers requires substantial computational resources.

This property underpins many password verification systems: passwords cannot be stored in plaintext on servers, so they are processed using cryptographic hash functions, and only the resulting hash value is stored. Recovering the original password from the hash is practically impossible, but verifying an entered password is straightforward – by hashing it again and comparing the results.

However, one-way functions cannot be considered absolute protection: the emergence of new computational technologies, such as quantum computers, could potentially enable the reversal of these functions and the recovery of secret keys or encrypted passwords. Quantum cryptography offers a solution to this problem.

What is quantum cryptography?

The fundamental principle of quantum communication and quantum cryptography is to make undetectable eavesdropping on transmitted data impossible. To achieve this, information is encoded not in light pulses or electrical current fluctuations as in classical communication lines but in quantum states,.such as the polarization of individual photons. The laws of physics prevent the measurement of quantum states without detection: the very act of measurement alters the quantum state, enabling the communicating parties to detect any interception attempt.

While public-key encryption’s security is relative and potentially breakable in the future, quantum cryptography promises absolute security: quantum mechanics prohibits undetectable interception of quantum communication.

The fundamental principles of quantum information protection were formulated in the 1960s-70s by Stephen Wiesner, Charles Bennett, and Gilles Brassard. In 1984, Bennett and Brassard introduced the first quantum protocol for secure communication, Quantum Key Distribution (QKD), known as BB84.

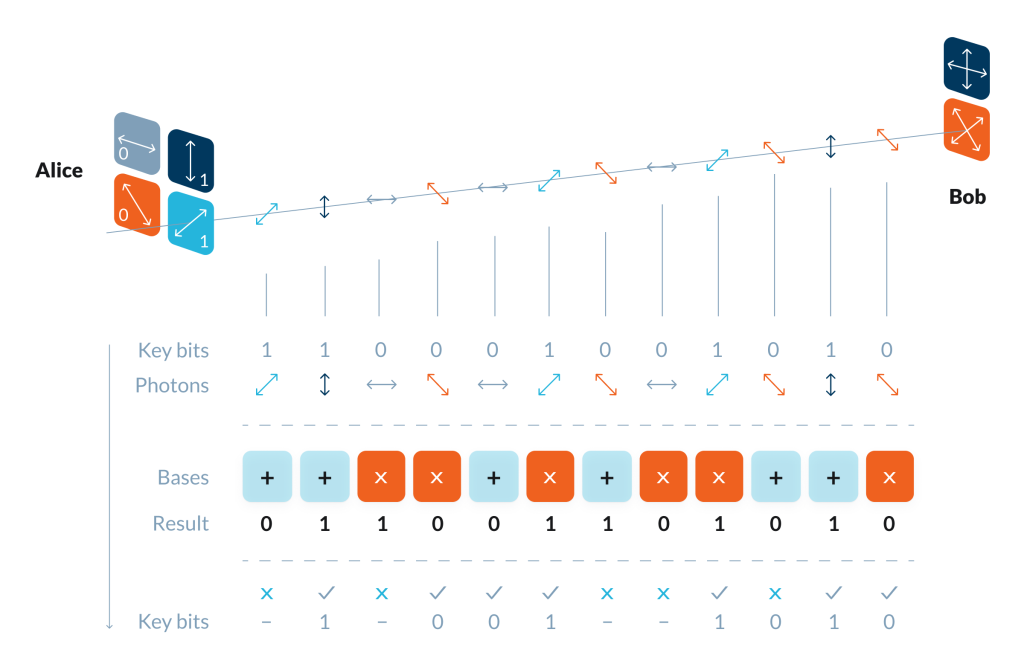

Data is transmitted with polarized photons. The sender (traditionally called Alice) polarizes photons in two different bases – such as 0°/90° or 45°/135° – randomly choosing bases for each photon. A bit value ‘1’ might correspond to vertical or 45° polarization, and ‘0’ to the other two orientations. The receiver (Bob) also randomly selects measurement bases and measures photon states.

Later, Alice publicly announces her bases over a normal channel. Bob discards the bits where his and Alice’s bases did not match (“sifting the key”) and tells Alice which bits were discarded. They end up sharing a common secret key, a string of zeros and ones, which both can use for encryption.

If an eavesdropper (Eve) tries to intercept, she has to measure the photon polarization, causing disturbances detectable by Alice and Bob. They simply discard the corrupted bits, leaving Eve with no information.

The main challenge with quantum cryptography is the fragility of photon states – they can be altered by thermal noise, fiber defects, and other factors, leading to decoherence and limiting the distance quantum communication can cover. For example, the BB84 protocol reaches its upper performance limits at approximately 2.38 Mbps over 25 km and only 0.052 Mbps over 70 km.

In classical communication, signals can be amplified with repeaters to reach any distance. However, amplifying quantum signals requires measurement, which means reading the photon states to obtain the key. This results in the need for a “trusted node” in the chain – a repeater node that is trusted not to leak information. This substantially reduces security.

Physicists defined a fundamental upper bound on secure key distribution rates without quantum repeaters – the PLOB limit (Pirandola-Laurenza-Ottaviani-Banchi bound). It restricts practical communication over distances like 300-400 km to tens of Kbps, challenging practical use.

Due to these limitations, quantum communication lines are still used only on a very small scale – for example, to connect bank offices within a city. In China, large-scale quantum networks spanning thousands of kilometers have been built, but all of them rely on trusted nodes. In other words, along the route from Alice to Bob, the secret key must be read and re-encrypted many times at intermediate stations. Chinese physicists are also conducting experiments on satellite-based quantum communication, which can enable secure links across continents. However, this approach requires very expensive infrastructure.

How to increase the distance of quantum communication?

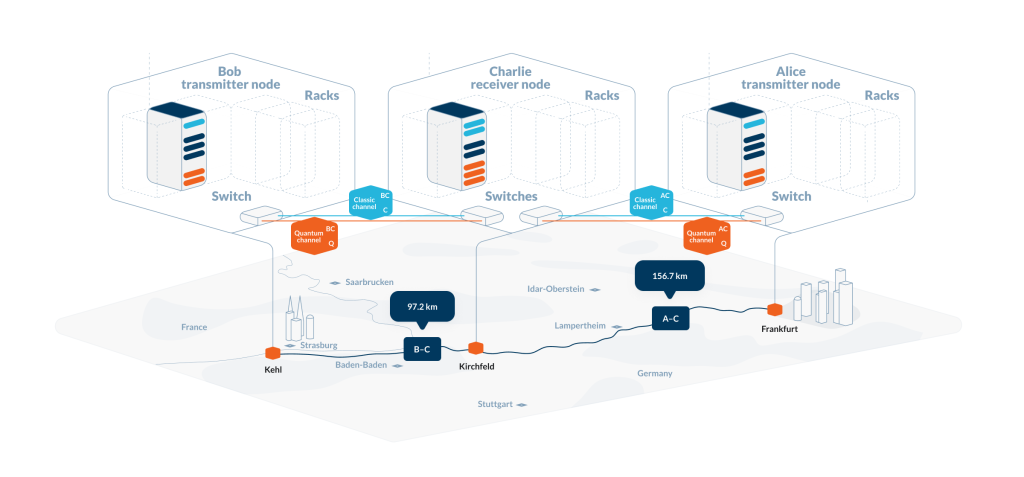

A team led by Mirko Pittaluga at Toshiba Research Laboratory in Cambridge (UK) demonstrated quantum state transmission over 254 km using the optical fibers of ordinary telecommunication networks, described in Nature.

For years, Toshiba physicists have been developing quantum communication based on the twin-field QKD (TF-QKD) protocol. In 2018, they overcame the rate-distance limit of QKD without quantum repeaters and achieved manageable noise over 550 km of standard fiber.

TF-QKD involves a third node, Charlie (an untrusted relay), located between Alice and Bob. Both send photons to Charlie, whose beam splitter directs incoming photons with equal probability of reflection or transmission. Information in this scheme is encoded in the phase: when the phases of Alice’s and Bob’s photons match, interference occurs, and due to the Hong-Ou-Mandel effect, both photons exit from the same side of the beam splitter. Charlie observes the outcome using two detectors positioned on either side of the beam splitter but cannot determine which phases Alice and Bob selected. Combining this information, Alice and Bob reconstruct a shared secret key.

Thanks to TF-QKD, photons only travel half the distance (Alice/Charlie, Bob/Charlie), so transmission rates scale with the square root of the distance, extending the range significantly compared to standard QKD.

The Toshiba experiment used existing telecom fibers between Frankfurt and Kehl with a relay at Kirchfeld, not specially built high-quality fibers. Instead of expensive superconducting nanowire single-photon detectors (SNSPD), the system used avalanche photodiodes (APD), which operate at higher temperatures and are far cheaper, greatly reducing system cost.

The apparatus was installed in standard telecommunication racks alongside existing classical equipment. The link distances were 156.7 km (Alice to Charlie) and 97.2 km (Charlie to Bob), operating continuously for 7.5 hours. Although the key rate was modest (110 bps), it set a record for quantum communication using commercial components.

Mirko Pittaluga noted, “This work opens the door to practical quantum networks without needing exotic hardware. It lowers the entry barrier for industry adoption.”