FemTech is now a familiar word in pitch decks and policy memos. It is far less familiar to the people it claims to serve: in 2023 among women aged 25–34, 40% in the US say they don’t know what it is. Women’s health research remains chronically underfunded, with just 5% of global R&D funding going to women’s health in 2020, and most of that concentrated in cancers and fertility.

This is where the FemTech story becomes more specific: pelvic pain and endometriosis, breastfeeding – high-friction problems that patients and clinicians keep ranking as priorities for better tools.

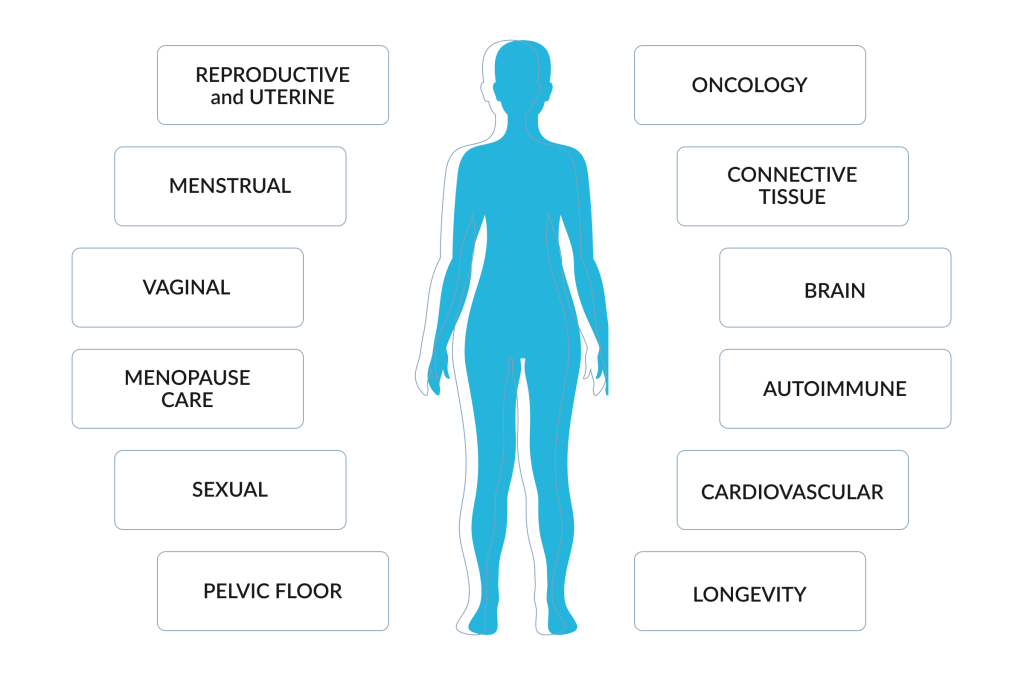

Femtech – is any technology, companies, and services that focus on the unique healthcare needs of females.

The word itself was coined by Ida Tin in 2016, and quite fast FemTech became a noticeable domain within digital health. But we have always had products for women, why invent a separate word now? For example, in 1901 Gillette introduced the safe easy-to-use shaver. Initially for men, but already in 1915 – special series for women. Sounds like the precursor of FemTech ? Not really.

With shavers the incentive emerged when the men’s market for the product hit saturation – every guy had his razor. So the market came up and successfully sold the idea of women’s shavers, more precisely – an idea, that hair on women’s bodies is unacceptable and should vanish. Humanity quickly took up arms against it.

So we definitely had items for the female part of the society, but like in this case, the attitude was mainly about pushing narratives that sell.

At its core, the entire FemTech concept re-envisioned women not as passive recipients of innovations, but as active participants driven by knowledge and curiosity instead of shame.

Businesses have always been struggling with finding new target audiences, and suddenly, we have noticed a huge group – half of humanity with unaddressed health needs.

What drives FemTech, what impedes it, what makes it different

The sector is clearly distinct, with its own specific traits that make it different from general healthtech. The first pitch deck looks like every other: a tidy problem statement, a clean UI screenshot. Then the founder says the actual thing out loud – what the product is about. Menstrual cycles. Sexual health. Fertility. Menopause. Sometimes a partner’s access. In most rooms, the air changes. The topic is awkward, “personal”, “niche”. Which is an efficient way to say: not built into the default assumptions of medicine, funding, or product design.

The first driver of FemTech innovations is discomfort, born as a pushback against prevailing conditions. And it keeps working like a pressure differential: the more a system treats an entire physiology as a “special case”, the more entrepreneurs treat it as a primary market – with its own data, edge cases, and failure modes.

A second driver is the research vacuum. A 2024 Nature Reviews Bioengineering editorial notes that women’s health research has been systematically underfunded, citing estimates that only a small slice of global R&D funding goes to women’s health beyond cancers.

In that context, femtech often functions as a scaffolding industry, building the basic frameworks that make missing data collectable and usable in research and care.

The third driver is labor economics disguised as “benefits”. As women’s participation and seniority in the workforce rose, employers began paying for what healthcare systems were slow to deliver: fertility support, pregnancy and postpartum care, menopause support. That matters because it creates a type of buyer who is neither the patient nor the clinician, but a budget-holder. That changes what the product path to success looks like – many companies start direct-to-consumer to prove demand, then pivot toward B2B or B2B2C once capital arrives and the “who pays” question becomes unavoidable.

Now, what impedes it.

Start with money – the mismatch between what investors are used to funding and what women’s health often requires. Because baseline research is thin, founders end up financing discovery work that, in other therapeutic areas, would be someone else’s job. That extends timelines and makes “quick exits” rarer, which then becomes the reason capital stays cautious – a loop that is hard to break.

The bias. Startups with at least one female founder are the majority in Europe, yet they raise less on average than all-male teams.

Then regulation. Intimate data, shifting reproductive politics, and products that slide between “wellness” and “medical”. The BMJ’s 2025 analysis argues femtech doesn’t necessarily need a wholly separate regulatory regime, but it does need heightened privacy and security safeguards because reproductive and sexual health data are vulnerable under social and political pressures and can become weaponized.

The same BMJ piece points to the post–Roe v Wade landscape in the US, and to Europe’s own fault lines, including Poland’s 2022 pregnancy registry. Critics warned it could make miscarriages and pregnancy terminations easier to scrutinise under one of Europe’s most restrictive abortion regimes. In that climate, both patients and clinicians can become more guarded: less disclosure, more defensive documentation, and, for some, hesitation or delays in managing pregnancy complications amid fear of criminal exposure.

Femtech collects health data in the legal sense, but also “intimate” data in a cultural sense, and those details can become dangerous when laws change or when people live under coercive regimes. The same tools sold as autonomy can potentially act as infrastructure for surveillance and control, with private firms ending up as intermediaries around reproductive rights.

And that leads to what makes femtech different from general healthtech.

First, the data is extremely “sensitive”.

Menstrual cycles and pregnancy status are not like step counts. In the wrong context, they can expose legal risk, coercion risk, or reputational harm. This makes privacy and trust a product feature in the deepest sense.

Second, the product boundary is unstable. Many solutions live in the consumer layer, yet they produce outputs that influence clinical conversations, affect fertility decisions, or invite “medical” interpretations. Regulators often hinge obligations on intended purpose and claims; founders learn to write marketing copy like lawyers, because one sentence can turn a lifestyle tracker into something that behaves like a medical device in the eyes of oversight.

Third, the market is structurally multi-payer – each with different evidentiary thresholds and different incentives.

FemTech startups can look like typical digital health companies on the surface, yet have a higher “mortality rate” underneath. Research on FemTech startups’ innovation dynamics points to the importance of early-stage market scoping and partnerships as survival infrastructure: clinical credibility, distribution, and the long slog of aligning a product with a real procurement pathway.

Woman who invented the FemTech market

Ida Tin didn’t exactly fit the mould of the Silicon Valley tech entrepreneurs when she discovered an entire domain. A Danish entrepreneur who originally set out to study art, in 2012 she co-founded Clue – a menstrual health app, that now has 100M+ аpp downloads and has raised $56M in funding.

Today the story of Ida Tin has made its way to the marketing textbooks, but as it often happens, a path to success was not that obvious in the beginning. Tin herself says that it was hard for her to get into the business world “I literally got lost in the hallways and I ended up in some office where they were waiting for a candidate to do [the business course interview],” Tin said as she explained her first steps.

Yet she was the one who finally cracked the taboo around the word “menstruation” and successfully raised funding for the period-tracking app.

When she began pitching the startup to investors, she was often the only woman in the meeting room. Once, a man across the table told her, “I only invest in products I can use myself.” Even some who recognized the business case seemed uneasy about the topic. One of the investors, who eventually put in a small sum agreed only on the condition that his participation stay confidential.

“I think there’s an unconscious bias that investors have, where they tend to invest in things they can emotionally connect to. I find that many men intellectually understand the product … but getting over that last little barrier and writing the cheque is harder,” she told the Guardian

Tin spotted a social dynamic where the strongest campaigns emerged at the moment something long kept out of view, starts entering in the mainstream. She made menstruation speakable by launching a campaign, documenting more than 500 slang terms for periods from around the world. That sparked media curiosity and a sense of recognition for people who rarely saw their experience named in public.

The company describes its mission as providing trustworthy information, data-driven tools, and emotional support for everyone with a menstrual cycle — as an empathetic, scientific companion from first period to last period.

By the end of 2025 Clue is still one of the most recognizable apps in the sector, but has 158 active competitors.

Tin decided to leave the CEO position in 2021 when the birth control app was approved by the FDA as a medical device.

“I could see that the things that I would have had to learn to really serve the company were things I’m not that good at, and I was not so interested in a lot of very serious operational stuff and that didn’t excite me as much,” Tin said.

“If you don’t think you can serve well enough or you’re not the best one to serve, then it’s good leadership to go, absolutely,” she added.

FemTech market

It still hides inside generic buckets like “health & fitness”, “wellness”, and “lifestyle” – yet consumer adoption is already mass-scale. A 2024 study briefing from the University of Oxford noted that three apps alone (Clue, Flo, Period Tracker) exceeded 250 million downloads combined.That kind of reach is hard to square with the old framing of women’s health as “niche”.

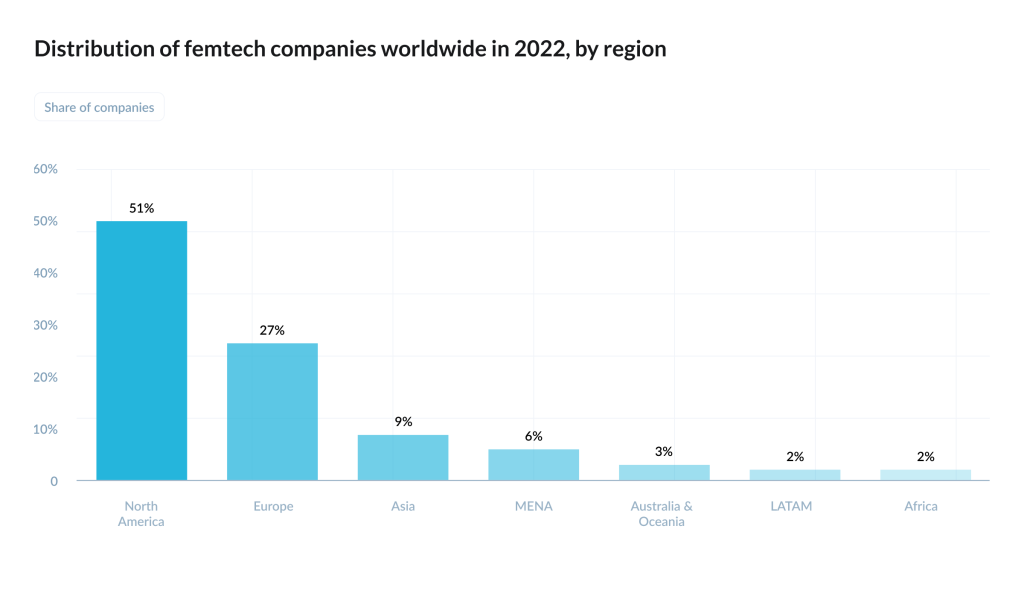

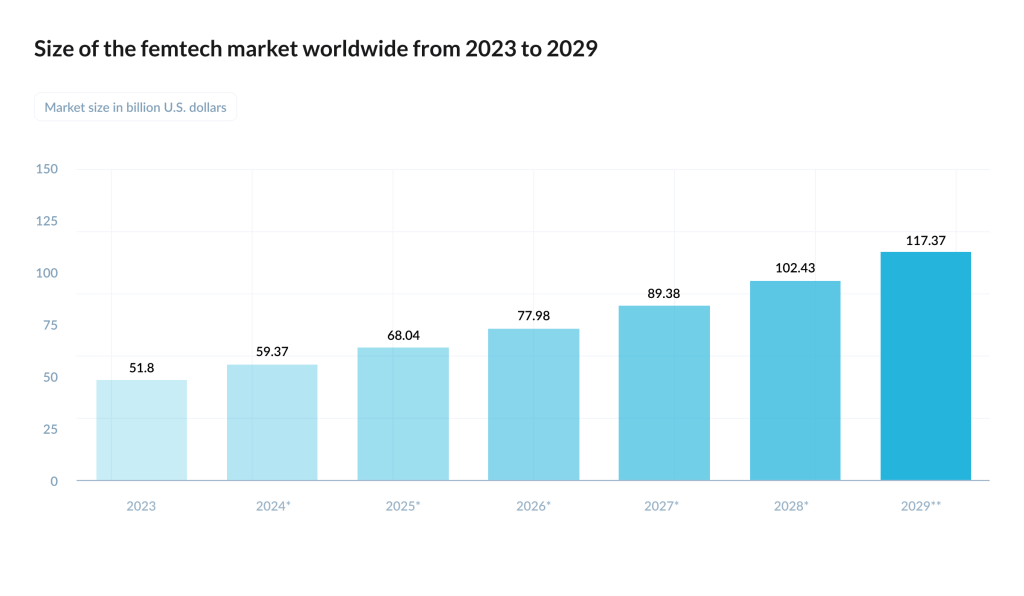

The money story is less linear. On paper, Dealroom estimated femtech companies’ combined enterprise value at about $28bn in 2024. In Europe, Sie Ventures’ mapping counted 540+ active femtech companies across the region, but also described the market as early-stage heavy – many pre-seed/seed, many not venture-backed at all.Their report projects the European femtech market exceeding $35bn by 2032, while documenting a persistent funding asymmetry: female-founded femtech startups are common, yet all-male teams raise more on average.

The “research vacuum” has its representation in funding: a 2024 Nature Reviews Bioengineering editorial put women’s health research at 5% of global R&D funding in 2020, with just 1% going to women-specific health conditions beyond cancers.

In parallel, women’s health has become a major generator of person-generated health data: a 2024 JMIR review found 406 papers (2015–2020) using digital tools that collect PGHD, with most studies focused on pregnancy/postpartum, cancer survivorship, and menstrual/sexual/reproductive health. A large share is still at feasibility or acceptability stage.

This is the market logic behind so many “simple” tracking products – they are data pipelines built in a landscape where baseline datasets are missing.

The next phase looks more regulated and more political at the same time. Some products are crossing the line into formal medical-device territory, for example, Clue Birth Control received FDA 510(k) clearance in February 2021 as a Class II “software application for contraception”. Meanwhile, the sector’s defining asset – intimate data – is increasingly treated as a liability surface. Ethical and legal analyses have warned that FemTech data can become “evidence” under shifting reproductive laws and coercive environments, and that privacy safeguards in consumer FemTech often lag behind what would be expected in clinical systems.

Female technology

FemTech still isn’t a household word. Among women aged 25–34, 40% in the U.S. and 46% in the UK reportedly didn’t know what “femtech” was. In Japan, 78.3% of women (as of 2023) were not aware of the term.

That looks like a marketing problem. It might be the opposite.

A sector stops being a “sector” when it turns into plumbing. Nobody checks out at a supermarket thinking about “fintech”; it’s just the card reader doing its job. The more women’s health tools move from novelty into routine care pathways, reimbursement logic, and boring procurement checklists, the less likely anyone is to remember the label that once made them legible to investors