Employees of the research division at Google Quantum AI have, for the first time, managed to run a “verifiable algorithm” on a quantum computer — an advance they say opens the door to the first practical applications of quantum computing. Moreover, their colleagues at UC Berkeley have demonstrated one such possible application: calculating NMR spectra of chemical compounds.

This new work doesn’t quite constitute a revolution in quantum computing, but it offers a good moment to pause and assess a field that, just a few years ago, dominated headlines before somewhat receding in the shadow of revolutionary LLMs. What’s actually new about this “verifiable algorithm” compared with previous efforts? What does “verifiable” even mean in this context, and why is Google emphasizing this term so strongly? What task does the algorithm perform, and does it have practical value? And finally: what might quantum computers of the near future actually look like?

In computing, “quantum” does not automatically mean “powerful.” Yet quantum computers can already tackle tasks that may remain out of reach even for today’s most capable supercomputers.

Any discussion of quantum computers must begin by dispelling the most widespread myth. No —quantum computers are not simply ultra-advanced supercomputers. They are not inherently faster, nor are they obliged to outperform classical machines. What makes a device “quantum” is only one thing: its ability to process quantum information. Even if this ability yields no speed-up for a particular task, the device remains a quantum computer.

But this property — the ability to manipulate quantum information — holds the promise of doing things that have so far been literally impossible, from breaking modern cryptographic schemes to predicting new materials with tailor-made properties.

So what exactly is quantum information, and why does it matter? In ordinary computers — those that “think” in 0s and 1s — the fundamental unit of information is the bit. A bit is a physical system that can store one of two values: 0 or 1. Assemble enough of these systems and you have memory; move them around according to predefined rules and you have computation.

Quantum computers replace bits with qubits, or quantum bits. Surprisingly, a qubit can also hold 0 or 1. So what’s the difference? A profound one.

A qubit stores information in a kind of sealed state: it can be both 0 and 1 at the same time — but only until you try to measure it. You’ve almost certainly heard of Schrödinger’s notorious cat — a thought experiment involving a feline trapped with a randomly triggered vial of poison. The point is that, in the quantum world, the cat is neither alive nor dead until you open the box. And this isn’t just epistemic uncertainty; the system is genuinely in a hybrid state.

A qubit is Schrödinger’s cat — capable of lingering in a superposition of 0 and 1.

This ability is what excites theorists and fuels massive investment: quantum computers could rethink how certain computations are performed.

Imagine a complex task that yields a single answer but requires brute-force search through many possibilities. Classic example: factoring large numbers, a problem central to modern cryptography. A classical machine must examine all candidates one by one.

But imagine a device that doesn’t operate on 0s and 1s, but on superpositions — “closed boxes” containing both. If the device is engineered so that its final output is definitively either “success” or “failure,” then in principle it can reveal the correct answer in a single step. If any valid solution exists among the many superposed possibilities, the quantum system can amplify its probability and surface it — no explicit search required.

Reality, of course, is more subtle. But this thought experiment hints at the essential distinction between classical and quantum computation.

It also explains why quantum computers will not replace classical ones — now or ever. Most daily tasks involve predictable transformations of information, not brute-force search over vast spaces. Quantum computers will complement rather than replace conventional machines, yet their impact could be transformative. Cryptography, machine learning, and numerical modeling of physical systems are areas where quantum methods may upend the landscape within decades.

Quantum computing follows an Anna Karenina principle: all classical computers are made of silicon, but quantum computers are built in astonishingly diverse ways.

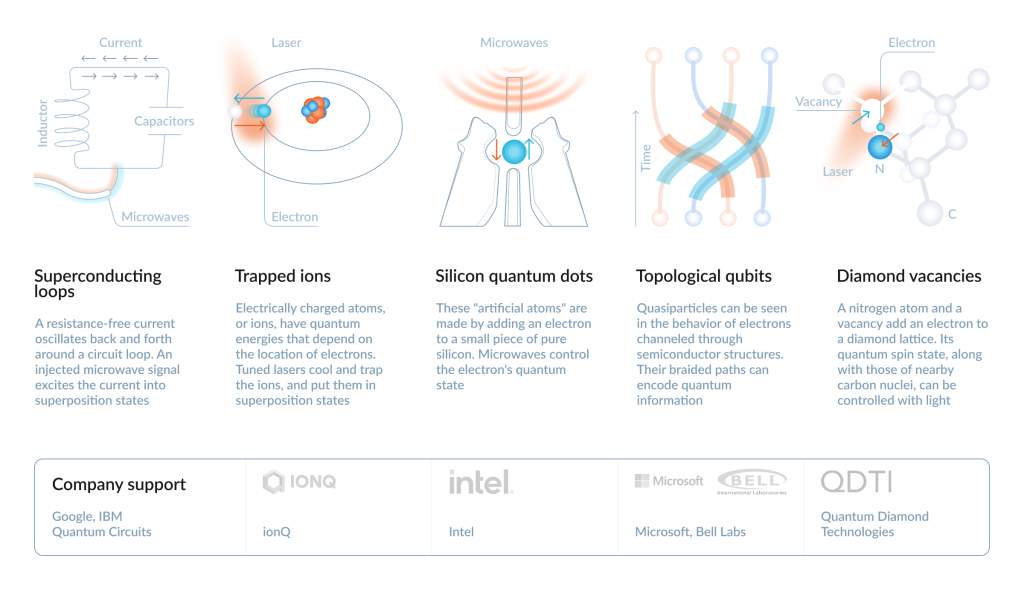

As we’ve established, what makes a system quantum is the type of information it processes, not the hardware itself. Modern quantum devices reflect this variety: nearly a dozen competing platforms attempt to store and manipulate quantum information, only some of which are shown in the infographic below.

Today, the most common — and arguably most promising — approach uses superconducting circuits with Josephson junctions. The details are rich enough to fill physics textbooks (and, incidentally, earned their inventors the 2025 Nobel Prize). In essence, these chips form a grid of tiny superconducting loops capable of storing quantum states as circulating currents. One such chip can house dozens of qubits (Google’s latest chip contains just over 100). The qubits interact with one another, and by finely controlling the strength of these interactions, researchers can perform computations.

Other approaches could not be more different. Some platforms use individual atoms — nature’s most pristine quantum objects — held in optical traps. Companies like ionQ exploit the fact that modern laser technology can isolate and manipulate single ions with remarkable precision. Although such atoms interact weakly with one another, making computation slower, they can preserve quantum information for long durations, making them an attractive quantum memory.

Another approach uses “vacancies” in diamond — tiny defects where a carbon atom is replaced by, say, nitrogen. These nitrogen-vacancy centers, used by companies like QDTI, behave like trapped atomic qubits embedded directly in solid matter.

Google, for its part, has long bet on superconducting circuits, and that bet has aged reasonably well. Competitors like Intel and Microsoft pursue radically different qubit technologies — quantum dots and topological qubits — both built from silicon using methods borrowed from classical semiconductor engineering.

This “qubit zoo,” as some physicists fondly call it, reflects the uncertainty of the field. No one yet knows which platform, if any, will dominate. Superconducting qubits currently lead in tested device count, but that could change quickly.

Doing what no one else can do is not the same as doing something useful. Nowhere is this clearer than in today’s quantum devices.

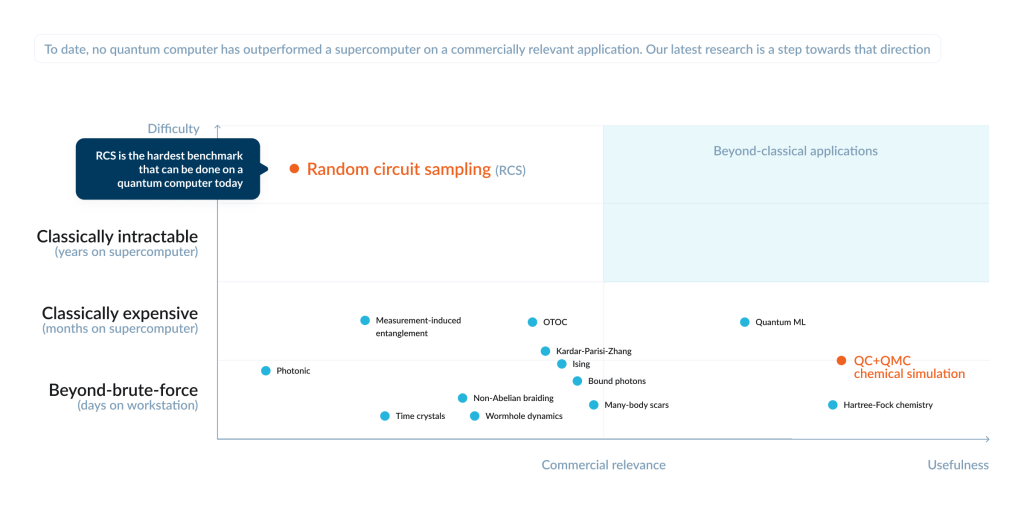

Before discussing Google’s new results and why the company emphasizes the “first verifiable quantum algorithm,” we need to revisit the concept of quantum supremacy — a term that has sparked heated debate. Coined by physicist John Preskill in 2012, the idea is simple: at some point, quantum devices will solve problems that classical computers cannot solve in any reasonable time.

Random circuit sampling. Тo date no quantum computer has outperformed a supercomputer on a commercially relevant application. Our latest research is a step towards that direction

In 2019, Google announced it had achieved quantum supremacy using its Sycamore chip. A calculation that took Sycamore 200 seconds would, they claimed, take the Summit supercomputer 10,000 years. IBM challenged the exact figure (reducing the estimate significantly), but the deeper criticism was more fundamental: the problem solved—random circuit sampling—was purely artificial. It had no practical value and couldn’t be reproduced on other devices. It was essentially a quantum “one-armed bandit,” producing random patterns that no one could replicate.

The new work marks progress on two fronts. First, the experiment — dubbed “quantum echo” —can be reproduced on other quantum devices, provided they meet certain quality thresholds. Second, Google and UC Berkeley have illustrated at least one plausible real-world application.

So what exactly did Google do?

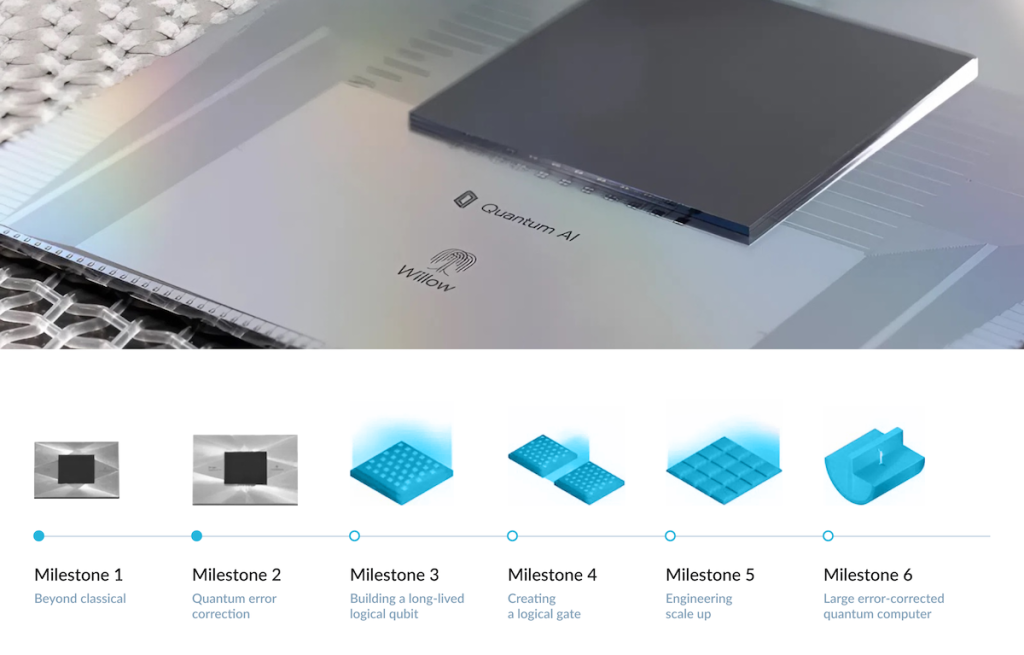

The experiment was performed on Google’s latest chip, Willow, introduced in late 2024. Willow is an evolutionary upgrade to Sycamore: nearly twice the qubits and, according to Google, better noise protection. Like all superconducting devices, Willow must be cooled close to absolute zero so its circuits can enter a superconducting state. This requires a massive helium-based refrigerator, which isolates the chip from environmental disturbances while still allowing researchers to manipulate and measure qubits.

As in the 2019 quantum supremacy experiment, the algorithm chosen was intentionally difficult to simulate on classical machines.

A metaphor helps: imagine tossing a stone into a pond. Ripples spread, reflect, interfere, and after some time, it becomes impossible to reconstruct exactly how they formed. But if you could reverse time, you could watch the waves converge back into the initial splash and see the stone re-emerge.

Google created a quantum analogue of this on Willow — not with water waves, but with currents in superconducting circuits. The “stone” was a deliberate perturbation introduced by the researchers. (If you want a more technical explanation, see this overview of out-of-time-order correlations and quantum chaos.).

Simulating this chaotic dynamics on a classical computer is extraordinarily difficult. Willow, however, performs it naturally.

The researchers ran thousands of such experiments, gathered statistics, and showed that the system behaves exactly as predicted. The “echo” caused by the perturbation can indeed be detected.

Initially, this experiment had no practical application; it served primarily to identify tasks well-suited to quantum devices. But a real-world use case soon emerged.

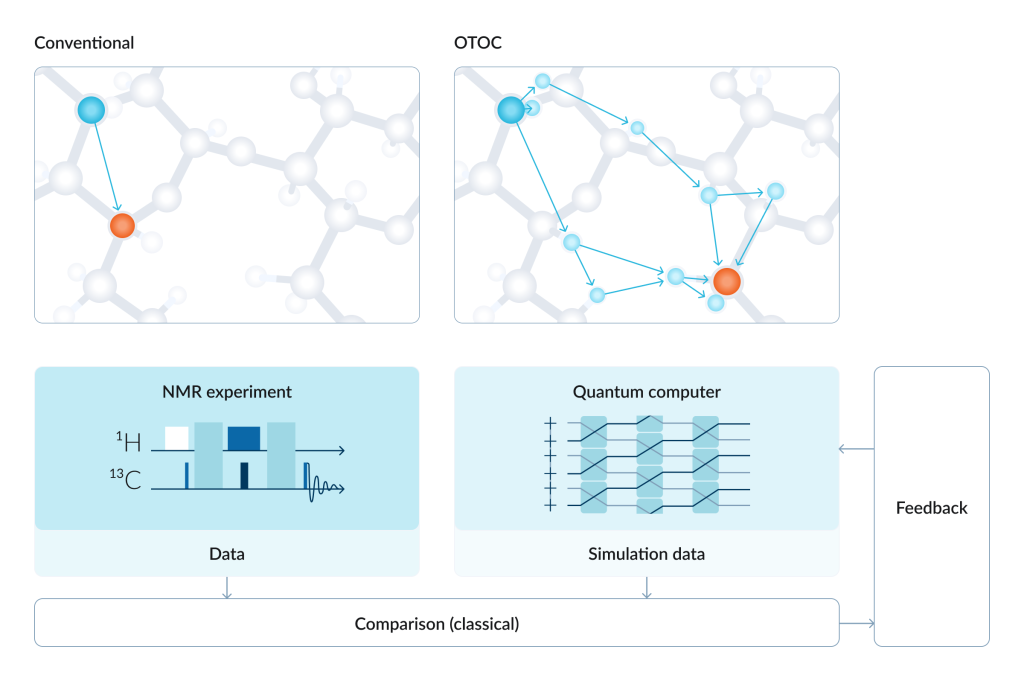

The team realized the same technique could be adapted for nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) – , a method used to probe molecular structure by analyzing how atomic nuclei interact in a magnetic field. In conventional NMR, chemists can usually infer interactions only among nearby atoms, as —long-range interactions are extremely difficult to detect.

But Google and UC Berkeley researchers showed that a quantum computer can help bridge this gap.

They first tuned the qubit-qubit interaction strengths (the “gates”) to mimic real chemical bonds, using conventional NMR data. Then they ran a “quantum echo” process analogous to the one described above: introduce a perturbation, measure correlations before and after, and analyze how individual qubits — standing in for individual nuclei — respond.

Google openly acknowledges that this is merely a proof of principle. Classical simulation of such small systems remains feasible. But the experiment hints at how quantum computers might one day analyze far more complex molecules — materials, catalysts, perhaps even drug candidates — that lie beyond classical reach.

The new work from Google Quantum AI showcases not only the field’s technical progress but also its trajectory. Quantum computers of the near future are unlikely to break RSA or run exotic algorithms — they will most likely become tools for exploring quantum systems themselves: small molecules, new materials, and perhaps innovative therapeutics.