Two years after ChatGPT’s introduction, there is little doubt that generative AI has had a profound impact on our lives. By some estimates, of all the technologies that are already massively adopted in the workplace, chatbots are the one we have adapted to most rapidly. Many studies show their impact in accelerating performance in a profession (1,2), but the question remains: what happens to this acceleration in the future, and can the economic impact of implementing generative AI in the workplace already be measured? A recent study conducted on a unique data sample from Denmark provides an unexpected answer to this question.

Denmark is one of the few countries where researchers can survey thousands of people in a wide variety of occupations and compare the responses with real data on salaries and hours worked. Anders Humlum from the University of Chicago and Emilie Vestergaard from the University of Copenhagen took advantage of this opportunity and surveyed 25,000 Danes who work in 7,000 companies across the country. The questions focused on how respondents use AI-chatbots (of any type) in their daily work, and the answers were compared to how this affects the respondents’ salaries and career development.

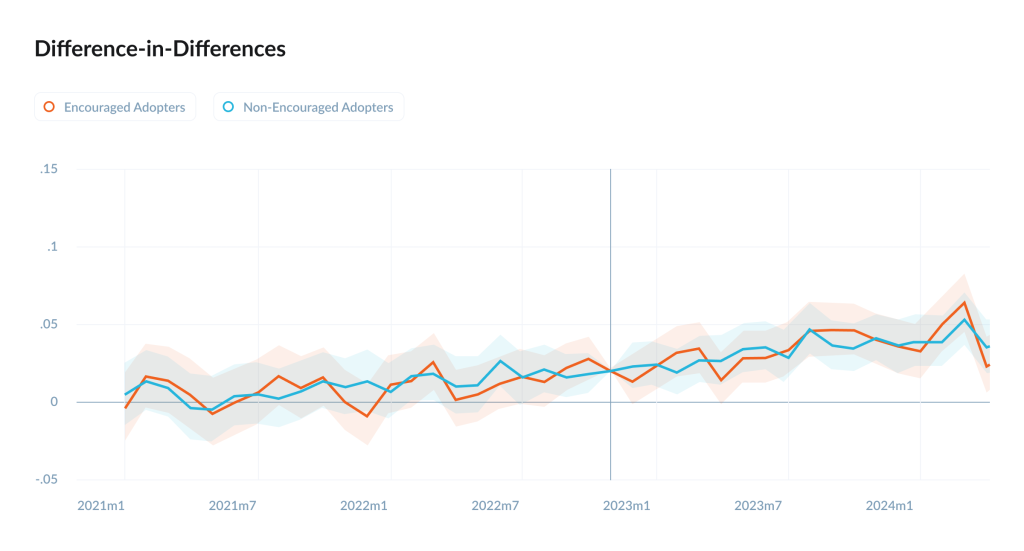

The economists used the classic difference-in-difference method for the analysis — i.e. they separated the data on those who often use AI and those who usually avoid it and then, for both sets, compared their answers before and after the mass spread of chatbots. It should be noted that the researchers were specifically interested in the most advanced (in the sense of adaptability to generative AI) professions: developers, marketers, lawyers, financiers, teachers, and so on.

You may not like the answer the scientists come up with in the article, but that’s what makes it interesting. It turns out that although the majority of respondents regularly use AI (8% – daily) and thus save working time (on average, 25 minutes a day), so far, the economic effect of chatbots in the workplace is strictly zero. “Our main finding is that AI chatbots have had minimal impact on adopters’ economic outcomes.” — to quote the authors.

The increased efficiency of old tasks doesn’t translate into increased wages or decreased total work time – at least not yet. Instead, it creates new tasks, often related precisely to the integration of AI into traditional workflow. Interestingly, according to the researchers, in 17% of cases, new tasks arise even for employees who don’t use AI themselves but work for a company that has already shifted some tasks to chatbots.

Adapted from: Humlum, Anders, and Emilie Vestergaard. Large language models, small labor market effects. No. w33777. National Bureau of Economic Research, 2025.

Strangely enough, this result does not mean that the introduction of AI is pointless from an economic point of view in principle. In reality, the picture is more complex and is not described simply by “robots will take away all our work” or “there is no benefit from AI.” There is a benefit, and the results of the polls have once again confirmed this.

The conclusions that the authors themselves draw from the article are different:

- First, AI-related productivity gains for workers are still very small (within a couple of percent, varying by occupation). Combined with the inertia of the labor market and the fact that such growth in principle never translates fully into wage growth, this gives the “zero effect” measured by the authors;

- Second, the authors note that they see the greatest growth where employers promote chatbots and introduce training programs for employees — a takeaway that executives should take note of. Not hourly pay, but at least job performance and job satisfaction in such companies grows more than the average;

- Third, the emergence of new tasks that accompanies the automation of old ones, as detected in the survey, is not some terrible drawback of modern AI but an effect well described by economists. It accompanies any automation of labor, and in this sense, the emergence of chatbots is not much different from the invention of the steam engine. So far, automation generates new tasks only within the existing professions, but historically, this has always led to the emergence of new ones, and there is no reason to think that this will not happen this time too.

Interestingly, at least two studies have been published since the release of the new research, which add important context to the Danish paper. The first study, conducted by Erik Brynjolfsson of Stanford University and his colleagues, is based on data from the U.S. market. The second study, conducted by Bouke Klein Teeselink of King’s College London, is based on data from the U.K. market. Both studies lead to the same conclusion: although, according to Danish data, chatbots do not yet affect the income of employees within companies that use them, they significantly reduce income growth opportunities for those outside the company. In simple terms, chatbots significantly reduce job prospects, especially for junior-level positions.

Adapted from: Brynjolfsson, Erik, Bharat Chandar, and Ruyu Chen. “Canaries in the coal mine? six facts about the recent employment effects of artificial intelligence.” Stanford Digital Economy Lab. Published August (2025).

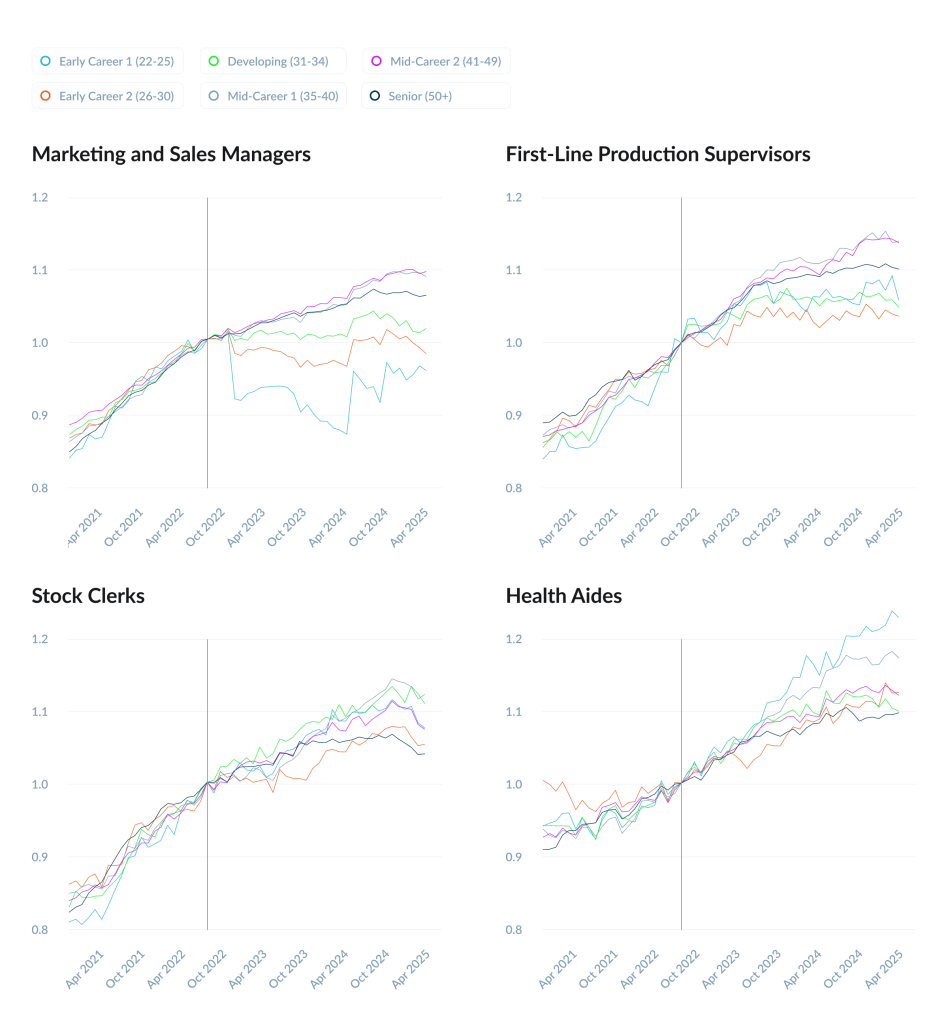

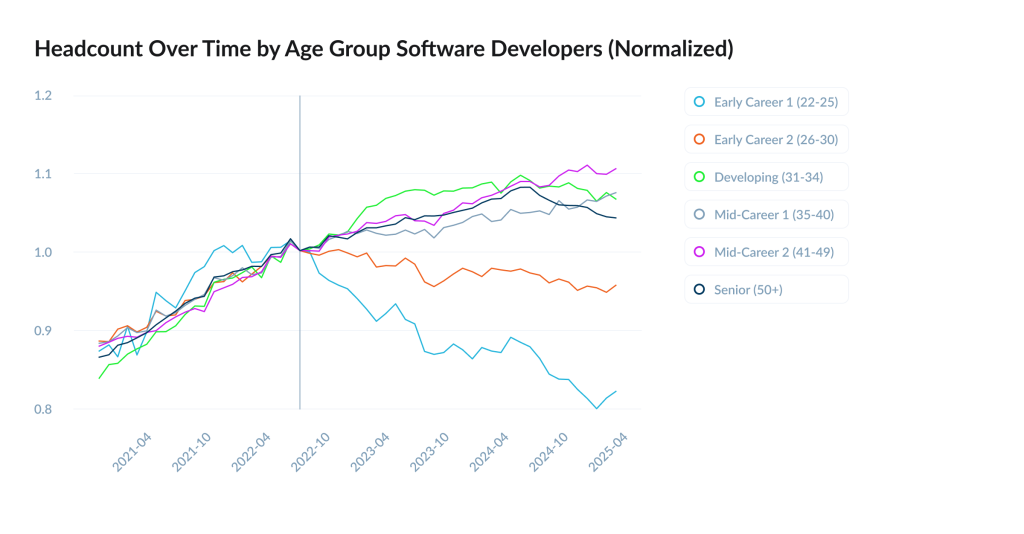

The graphs below clearly illustrate this with the example of software developers: after the widespread adoption of chatbots, the number of young developers (under 30 years old) declined, although it continued to grow among more experienced specialists. While not all professions experienced this effect as strongly or clearly as developers did, age proved to be an important factor in how much it affects candidates’ chances of getting a job in many other professions (see the last graph). The results of the Danish study can be better understood by considering this important context. The labor market as a whole is influenced by chatbots, even if they do not have an economic impact on the workplace. The influence of chatbots on the labor market depends on the age and experience of workers.