Artificial intelligence has rapidly become a working tool in companies, government administration, education, and everyday services within just a few years. As AI becomes more widespread, the question of “are we ready?” becomes increasingly important. How well is the infrastructure of a given country adapted to the integration of artificial intelligence? Are the rules of engagement clear? Can we speak confidently about data protection? How does this new, critically important factor influence the restructuring of the labor market? All this information is encapsulated in the AI Preparedness Index (AIPI), developed by the International Monetary Fund.

This analysis of a vast array of data consolidates four major “pillars”: infrastructure, human capital, innovation/integration, and regulation/ethics. According to its creators, the goal is not to determine “who is better,” but to understand where countries have bottlenecks in the process of implementing artificial intelligence. We discussed all of this in detail with Alexander Malyarenko, an economist and business analyst at Andersen, who has 15 years of experience researching the macroeconomics of Eastern Europe and the EU.

What is AIPI and why is it not a “leaderboard”?

2Digital: To begin with, could you briefly describe what the IMF’s AI Preparedness Index is and why it is needed, especially since there is so much debate about AI every day?

Alexander: It is not difficult to understand that a phenomenon that is changing the world before our eyes requires close attention to how prepared various countries are for it. AI is indeed appearing almost everywhere: sometimes because it is trendy, and other times because it delivers real results. The technology has already become mainstream, and there is a scientific challenge to understand how different countries can absorb this wave — businesses, society, and government.

The emergence of AIPI was an attempt to create a benchmark for measuring “readiness for AI.” In a way, it is similar to how GDP became a method for measuring “the size of the economy”: it is rough, imperfect, and sometimes highly debatable, but ultimately accepted by all. However, the AI Preparedness Index does not explain how to implement AI — that is the task of practitioners and engineers. It measures the fundamental parameters of the “foundation”; the higher they are, the greater the chance that AI-related projects in the country will develop more successfully and dynamically.

2Digital: The index speaks of “readiness.” Whose readiness is being assessed: society, business, or government? Can one be ready in one area and fail in another?

Alexander: Of course, we all desire simple answers, but there will be none, as “readiness” here is a synthetic concept composed of many distinct parameters. One country may have a strong startup and even a “unicorn,” but society may not trust the technology or lack basic digital skills. In another country, the population and companies may be ready, but there is no environment that allows innovations to scale successfully: for example, we see a weak investment climate, an imperfect R&D ecosystem, and low labor and capital mobility.

This is why AIPI is broken down into blocks that attempt to distill them to a common denominator. And yes, one can be “strong” in one block and “lag” in another — this is precisely what the index helps diagnose regarding the basic conditions and states for AI implementation in a given country. At the same time, it also assesses the overall potential of the country, taking into account its strengths and weaknesses.

Another important detail: like many other global studies, AIPI is released with a significant lag, so it is essential to remember that we are discussing an analysis for 2023, which in today’s context feels like “the last century.” Nevertheless, this information can still be useful, as it reflects general trends and will show them in dynamics over time.

2Digital: Such indices are often perceived as a “leaderboard.” Why does the IMF itself warn that this is more of a diagnosis of bottlenecks than a competition among countries?

Alexander: Because such macro indicators can significantly influence, for example, the attraction of investments to a country. This is what happened with Doing Business: it transformed from a universal marker for economists into a subject of political manipulation—leading to investigations and the discontinuation of the project. As we mentioned earlier, AIPI is a “mean temperature in a hospital,” which says little without further explanation. Two countries may have the same overall score, but the reasons for how it was formed can be diametrically opposed: one may have a strong labor market and legal framework but weak infrastructure; the other may have decent infrastructure but issues with institutions, trust in AI solutions, and the quality of regulation.

Four “pillars” of readiness: DI, HCLMP, IEI, and RE — what lies behind them?

2Digital: The index consists of four blocks: digital infrastructure, human capital and labor market policies, innovation and economic integration, regulation and ethics. What do these terms mean in real life?

Alexander: Let’s try to articulate this as clearly and concisely as possible:

Digital Infrastructure (DI) refers to “where you implement AI”: the availability and quality of connectivity, data centers/clouds, digital services, and the maturity of basic digitalization.

Human Capital and Labor Market Policies (HCLMP) pertain to who writes, implements, and uses all this. This includes STEM education and, more broadly, digital literacy, the ability of people to retrain, and worker mobility.

Innovation and Economic Integration (IEI) assess how vibrant the ecosystem of research and development, entrepreneurship, and investment is in a country, and how easily an idea can become a product and scale.

Regulation and Ethics (RE) involve data processing rules, accountability, protection, cybersecurity, and, crucially, the ability of the legal framework to “keep pace” with new digital business models.

2Digital: The index includes components based on expert/survey assessments, which implies a certain degree of subjectivity. In which areas is this particularly risky: trust, quality of institutions, ethics?

Alexander: The issue of trust in expert assessments is almost commonplace: surveys and interviews capture not only reality but often reflect the mentality of the measurer, the questioner, and the respondent. As a result, for example, the “level of trust in technology” may not be so much about the technology itself but rather about the social norm of asking and answering such questions.

The quality of institutions is even more interesting: many indicators are based on perception — how “independent” the courts seem, how clear the rules are, and how low corruption appears to be. These are important factors, but they are subject to politics, the country’s reputation, and even media waves. Additionally, institutional changes always lag in data — rules may have changed, but the “assessment” in indices will catch up later.

However, the most contentious area remains ethics and regulation: what is considered “normal” in different political-legal models often relies on different philosophical foundations.

The European approach (in the spirit of “safety first, then scale”) is risk-oriented: it imposes more requirements for transparency, accountability, and data protection. The EU has explicitly enshrined this in the EU AI Act, which came into effect on August 1, 2024, but is being implemented in phases: some norms (such as those regarding prohibited practices and AI literacy) will take effect from February 2025, the block concerning general-purpose AI from August 2025, and the majority of requirements from August 2026.

Sometimes, where experts often highlight advantages — rules and “safeguards,” businesses respond: “this means more costs and approvals: slower, more expensive, and less speed.”

The American approach to AI regulation is often described as decentralized: instead of one “big” federal law, there is a set of industry rules, regulatory decisions, and enforcement practices. This “mosaic” nature is detailed by the Congressional Research Service.

This logic also aligns with the NIST AI Risk Management Framework: it is a voluntary risk management framework rather than a mandatory standard. Such a model offers greater flexibility and speed of implementation. Its weak point is the risk of “overheating”: if the market quickly fills with raw solutions, the likelihood of scandals and loss of trust increases, after which the regulatory pendulum swings — requirements begin to tighten reactively in response to problems.

The Chinese approach emphasizes a high role for the state and governance through administrative rules, often focusing on safety, risk control, and content/distribution management. For example, the Interim Measures for Generative AI came into effect on August 15, 2023, along with related regimes for algorithmic recommendations and “deep synthesis” (labeling/control of synthetic content).

Ultimately, one expert may give a “plus” for feasibility and state power, while another may say “minus for freedoms and risks to an open innovation environment.”

Both will be sincere — simply viewing the issue through different value lenses. This is why subjectivity in such blocks is particularly dangerous: we are comparing not only data but also worldviews.

From pilots to scale: data, rules, and the labor market

2Digital: Let’s move on to the numbers. What does AIPI show, and how should we interpret the comparisons?

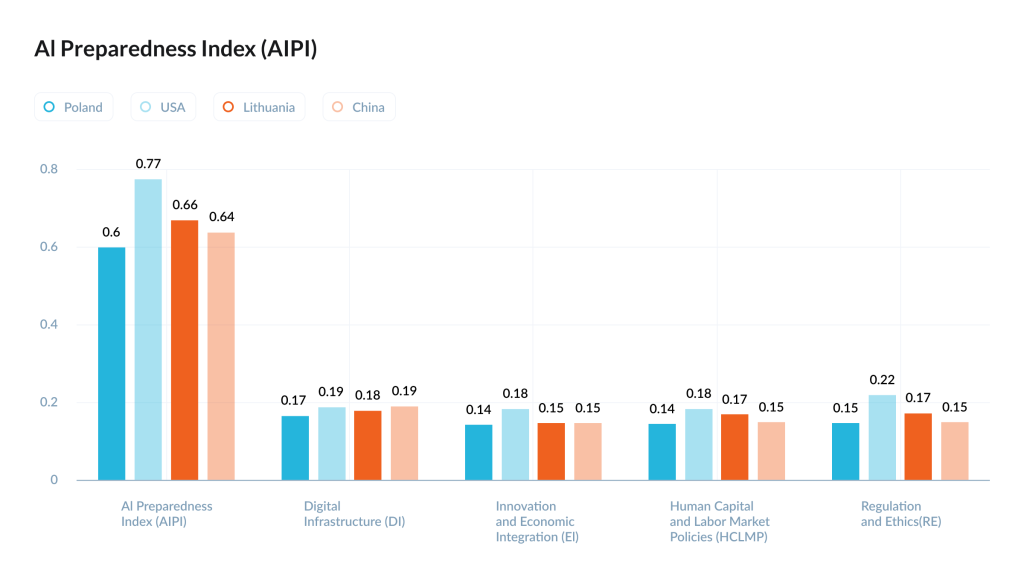

Alexander: When studying AIPI, it is essential to remember that it is the sum of four sub-indices (DI + IEI + HCLMP + RE). For example, the rating for the United States is 0.7713, for Lithuania it is 0.6649, and for China it is 0.6355. However, this is not about one magical number, but rather about which specific sub-indices have advantages and what they ultimately yield. Here, an important observation emerges: in terms of digital infrastructure (DI), the gap is not as dramatic — China is at 0.1901, the U.S. at 0.1878, Lithuania at 0.1774, and Poland at 0.1655. Thus, “internet and data centers” alone do not explain why the U.S. is pulling ahead; the decisive difference accumulates in the other blocks.

Where exactly the gap widens is evident in the three other components. The U.S. has a high Innovation & Economic Integration (IEI) score of 0.1825 (compared to 0.1476 for Lithuania and 0.1471 for China), a high Human Capital & Labor Market Policies (HCLMP) score of 0.1833 (Lithuania at 0.1684, China at 0.1499), and a particularly noticeable gap in Regulation & Ethics (RE) at 0.2177 (Lithuania at 0.1714, China at 0.1483). As a result, China may be very strong in “hardware/connectivity” (DI), but it lags in areas where it is crucial to quickly transform technologies into scalable businesses and safe mass-market products (IEI + RE). Lithuania demonstrates that a small country can indeed raise its overall index through a combination of skills/adaptability in the labor market and a more “ordered” regulatory environment compared to many developing economies (HCLMP + RE), even without the scale and capital of the U.S.

2Digital: What signs indicate that AI is scaling in a country rather than merely existing in presentations?

Alexander: Pilots usually end where three “boring” things begin: data, processes, and accountability.

A pilot can be assembled on enthusiasm and initial grants. Scaling requires:

– sustainable funding

– access to data and rights for processing it

– clear accountability (who is responsible for a model’s error)

– integration into processes (so that AI is not an artificial “overlay,” but a real part of the business)

– personnel who can support the solution post-launch.

The index helps understand why similar projects in one country “stick” to reality while in another they do not: in some cases, it is due to infrastructure, in others, societal trust, and in others, overly strict or, conversely, too lax regulation.

2Digital: There is a suggestion that the more “office” and service work there is in a country, the more AI will change the labor market. Is this true?

Alexander: Yes, there is a direct correlation. The more the economy is service-oriented and involves cognitive tasks — meaning work “by the head”: texts, calculations, analysis, communications, customer service — the easier it is to integrate AI. These are processes that already exist in a digital environment: documents, CRM, email, databases, chats.

If you have a sector where much is done manually and is hardly digitized, there is simply no place for AI to “attach.” For instance, if cows are milked by hand, AI is powerless there. If it is an automated farm with sensors, statistical accounting, equipment, and software, then AI becomes a real tool: optimizing modes, predicting failures, reducing losses. Thus, the question is not about the “profession” as a title, but about how digital and scalable the task is.

What would you prioritize to enhance the real readiness of the market for AI implementation, rather than a cosmetic one?

— First and foremost, in my opinion, it is essential to start with creating an environment. This is what the government should do first: set norms and rules of engagement. Its role is to be a facilitator that provides clear, comfortable, and safe conditions for working with AI — for businesses, universities, agencies, and citizens.

The key word here is elasticity. Regulation should be like a rubber band: on one side, it should tighten the sector together and protect (data, accountability, safety), while on the other, it should not become concrete that stifles growth right from the start. Because models change constantly, opportunities evolve literally every month, and if the framework is “not alive,” it either quickly becomes outdated and turns into a fiction or starts to stifle innovation. Therefore, my priority would be to gather and launch an adaptive legal and organizational structure that must evolve alongside technologies: clear data rules, clear accountability, and clear “corridors” for testing — so that AI develops not on the principle of “prohibit everything” or “do whatever you want,” but in a normal, safe “greenhouse” of innovation before entering the open market.