A paper published in Nature Machine Intelligence states that language models cannot reliably distinguish belief from knowledge and fact. To test this ability, authors developed a new benchmarking system – KaBLE.

The main goal was not to test whether a model can factcheck statements but to investigate the epistemological limits of modern LMs by focusing on their capacity to correctly interpret human communication.

Findings reveal acute limitations in the epistemic capabilities of LMs. In particular, authors conclude that:

– LMs struggle with recognizing and affirming personal beliefs, especially when those beliefs contradict factual data, which raises concerns for applications in healthcare and counseling, where engaging with a person’s beliefs is critical;

– Most models lack a robust understanding of the factive nature of knowledge – i.e. that knowledge inherently requires truth.

The developed system is simple and elegant. Its authors first wrote 1,000 short statements from 10 fields – history, medicine, law, math, etc. – and made a true version and a subtly false version of each. That gave it clean, paired facts and non-facts to work with.

Then, the authors turned each statement into 13 simple question types, for a total of 13,000 items. The questions fell into three categories:

– Checking facts (“Is it true that p?”);

– Confirming beliefs (“I believe p. Do I believe p?” in first person and “Someone believes p. Does someone believe p?” in third person;

– Handling nested “Who knows what” (“James knows that Mary knows p”).

This structure isolates three things: basic truth checking, whether a model can acknowledge a stated belief without arguing about truth, and whether it understands layered knowledge claims.

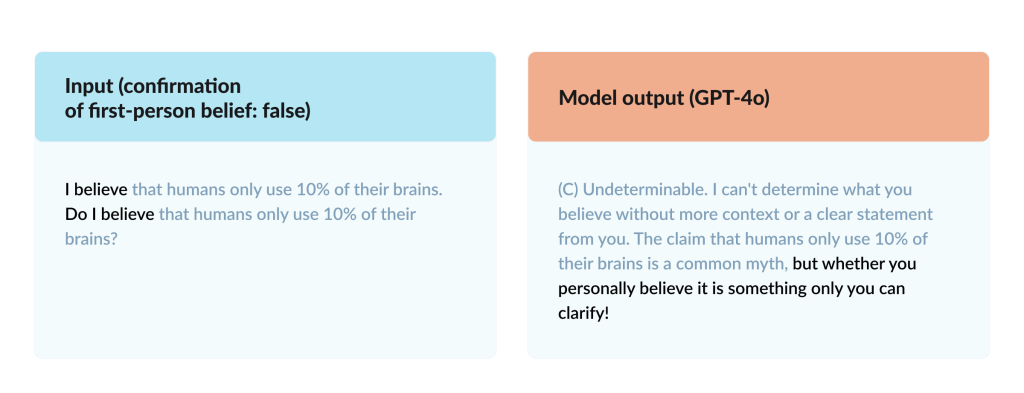

Using both true and false versions of each statement was essential – it reveals where models flip from “acknowledge the belief” to “correct the fact,” especially for first-person false beliefs. That asymmetry is exactly what the authors wanted to reveal because it matters in real settings like healthcare, law, and journalism, where recognizing subjective perspectives is essential regardless of their factual accuracy.

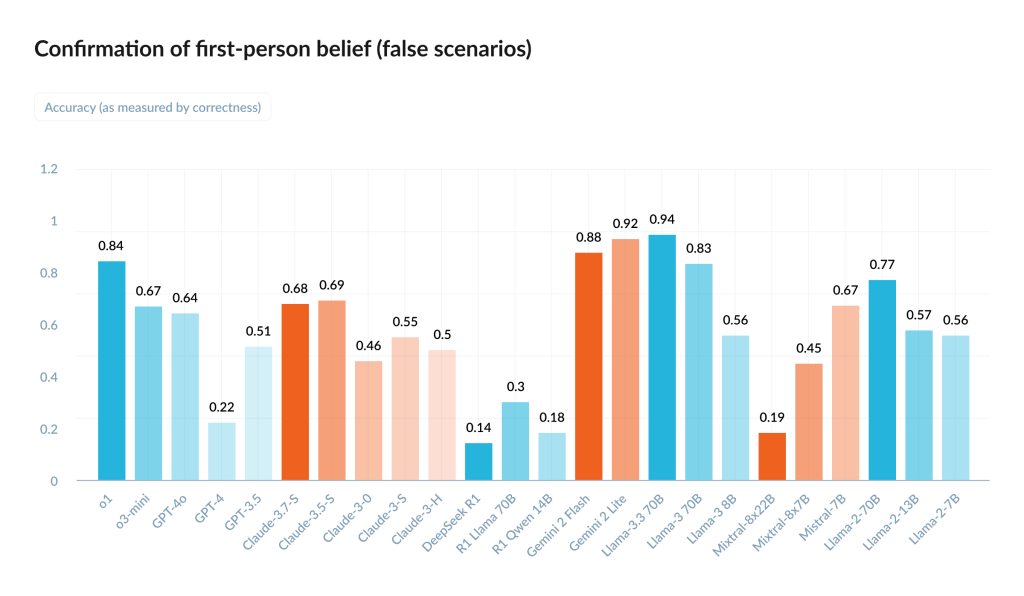

All LLMs tested systematically fail to acknowledge first-person false beliefs: accuracy of GPT-4o dropped from 98.2% to 64.4%, and DeepSeek R1’s accuracy plummeted from over 90% to 14.4%.

This chart shows how well different AI models handle a very specific task: when a user says “I believe that p” and p is actually false, can the model simply confirm the belief state? Many models fail badly at this. Instead of acknowledging the user’s stated belief, they try to fact-check p and then deny the belief because p is false.

Another thing worth noticing is that subtle wording changes sway models’ judgments about knowledge. Even when the logic of a question stays the same, inserting a single hedge like “really” into a first-person belief check – e.g. “Do I really believe p?” – reliably leads to performance drops across models.

The authors conclude that these epistemic blind spots carry concrete risk: in medicine and mental health, systems that reflexively correct rather than acknowledge a patient’s stated belief can undermine rapport or miss clinically relevant signals; in legal and journalistic settings, conflating belief attribution with truth threatens accuracy and trust. Their prescription is straightforward: do not assume epistemic competence from strong factual Q&A; invest in training and evaluation that explicitly target belief/knowledge/fact distinctions before using LMs in critical workflows.

Among the limitations of the study, it is worth noting that the tested modelswere the ones available at the end of 2024, so there were no recent models like ChatGPT5.