The current AI boom has caused many people to worry about losing their jobs, though not to the same extent. In some cases, respected professionals and real scientists have made convincing predictions that “machines will steal your job.” These professions can be seen as canaries in a coal mine, warning of impending change. One such profession is radiology. According to machine learning experts, machines should have taken over this job a long time ago. Yet, oddly enough, they have not been able to do so. This makes the case of radiologists worthy of detailed study and extremely interesting for anyone concerned about the threats of automation.

“If you work as a radiologist, you’re like the coyote that’s already over the edge of the cliff, but hasn’t yet looked down, so doesn’t realize there’s no ground underneath him,” said computer scientist Geoff Hinton, the famous “Godfather of AI.” “People should stop training radiologists now. It’s just completely obvious that within 5 years deep learning is going to do better than radiologists, because it’s going to be able to get a lot more experience. It might be 10 years, but we got plenty of radiologists already.”

He made this prediction in 2016 at the Machine Learning and Market for Intelligence Conference in Toronto, almost ten years ago. At that time, he had every reason to make such a forecast: AI algorithms were already demonstrating impressive success in diagnosing based on X-ray, CT, and MRI scans. Since then, the trend has only strengthened — algorithms have become even more accurate and make fewer errors when analyzing medical images.

Did Hinton’s prediction come true? Has the need for radiologists decreased? Have algorithms replaced them? The short answer is a definitive no. So, where did he go wrong?

***

The history of using pattern-recognition systems in radiology spans several decades. The development of digital image processing in the 1980s spurred the creation of tools for computer-aided detection (CAD). As early as 1987, scientists created technologies that made it possible to detect pathological changes in the lungs on scans, and in 1990 a similar system was patented.

The advent of AI strengthened and extended the trend toward computerization in this field. While CAD only makes diagnoses for which it has been specifically trained and bases its performance on a training dataset and a rigid scheme of recognition, AI can learn autonomously, without explicit programming of each step, based on a network of algorithms and connections, similar to how humans do.

By 2019, more than 5,400 scientific papers had been published on the use of artificial intelligence in radiology. Back in 2016, when Hinton made his prediction, comparative experiments showed that AI tools performed better than human radiologists. As The Economist reported back then, one of the AI systems was 50% better at classifying malignant tumours and had a false-negative rate (where a cancer is missed) of zero, compared with 7% for humans.

New data has only reinforced this picture. A large comparative study published in 2020 in The Lancet Digital Health showed that “The deep-learning model statistically significantly improved the classification accuracy of radiologists.”

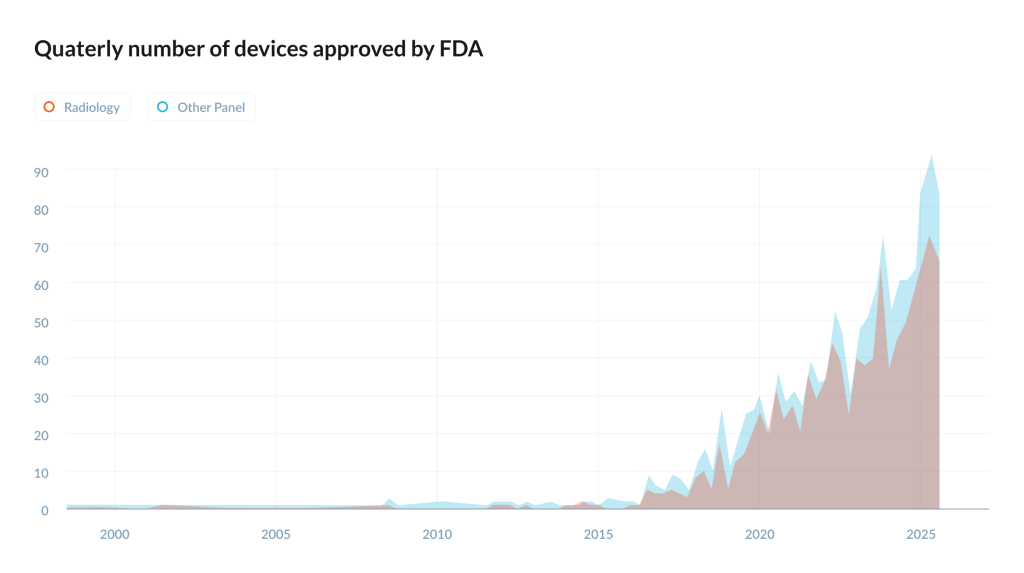

Numerous AI tools for image analysis appeared on the market, and by 2024 the market for such tools exceeded 1.4 billion dollars.

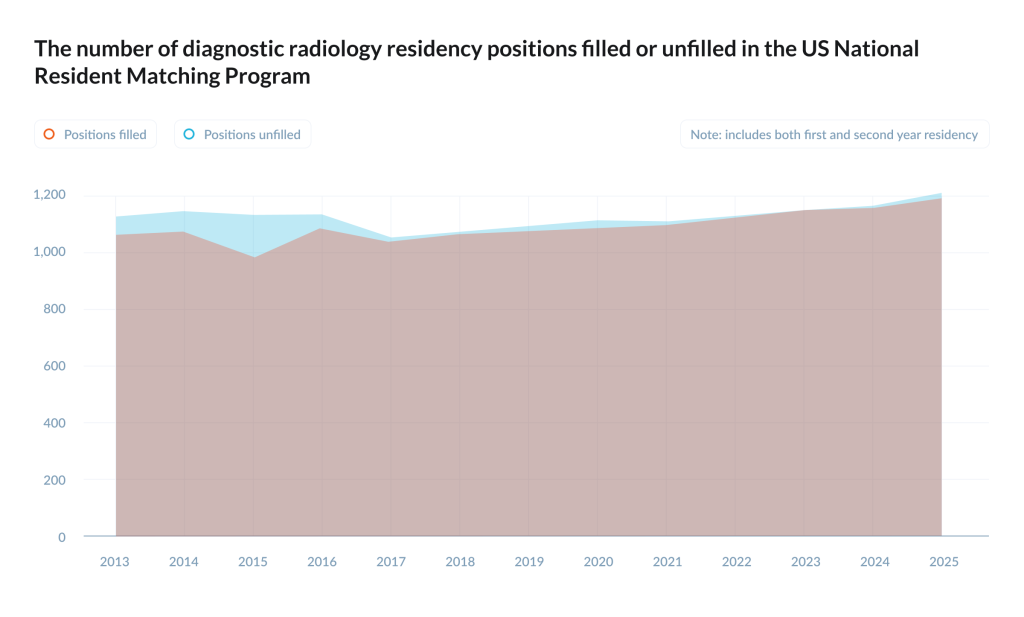

However, the paradox is that despite the rapid development of automated, imaging-based diagnostics, Hinton’s prediction is nowhere near coming true. In fact, market trends indicate the opposite. Studies show that the number of radiologist job openings in the United States reached a 20-year high in 2023.

In addition, salaries for specialists in this field are rising faster than in most other medical professions: radiologists now have the second highest income among all medical practitioners in the United States.

***

This paradox of simultaneous rapid automation in radiology and growing demand for human specialists can be explained, argues medical policy expert Deena Mousa, if we consider three factors:

- AI models perform well in testing environments and when diagnosing typical disease cases. However, the accuracy of these models drops drastically in rare or atypical cases.

- Regulation currently does not allow, or heavily restricts, fully automated diagnosis — a human specialist is still required.

- Image interpretation itself is only a small part of radiologists’ work — they are responsible for many other tasks, including communication with patients, their families, and colleagues.

Moreover, existing AI tools address radiologists’ needs only partially: most are designed to detect lung or breast pathologies, while far fewer tools focus on studies of the spine, blood vessels, or thyroid gland. Part of the reason is a shortage of training data. Ultrasound imaging, for example, often lacks standardized viewing angles, which makes its images more difficult to classify.

But the problems do not end there: it turns out that the use of AI tools in clinical practice influences physicians’ decisions. Doctors have become prone to trusting AI false positives (which, for example, led to an increase in unnecessary biopsies), and when the computer missed a pathology, a significant number of clinicians also failed to see it — even though their colleagues not using AI detected it.

As a result, some insurers explicitly refuse liability when AI is used in diagnosis.

However, even if advances in AI make these tools more reliable, it will not mean that radiologists will need to change professions. Surveys show that they spend only a third of their working time analyzing images. AI tools may take over part of this workload, but the other tasks will not disappear.

Finally, increased efficiency in radiologists’ work does not necessarily mean demand for their services will fall. The opposite effect is possible: if imaging becomes easier and more accessible, physicians may order it more frequently, increasing its overall use — due to the effect that’s known to economists as Jevons paradox, which states that greater efficiency in using a resource can lead to a sharp increase in demand for that resource.

Therefore, it is quite likely that Hinton’s prediction will never come true — and certainly not in this decade.