Teaching medicine is associated with moving tons of facts from a textbook into the brain. But other than that, it is about building mental models that support pattern recognition, calibration of risk, and an internalized sense of responsibility for other people’s lives.

AI came to the field of medical education as an enhancer, a “scaffold” for the learning process that can individualize feedback, simulate complex cases, and expand access to resources. In reality, it also obviates the practice and reflection process, eventually leading to deskilling of learners.

Adam Rodman and Avraham Cooper, the authors of the paper “AI and Medical Education – A 21st-Century Pandora’s Box” contemplate that tools able to generate plausible clinical reasoning and exam-ready answers risk blurring where the student’s judgement ends and the system’s judgement begins.

In real-life situations, patients and insurance companies are not asking for judgement as such; what is needed is a tailored response in a particular clinical scenario. Fast.

So when we have diagnostic tools that are better than novice specialists in answering questions, learners may be tempted to outsource thinking rather than develop it.

When Peyton Sakelaris’ group surveyed a full preclinical cohort, it turned out that students who used AI to simplify difficult topics did not achieve better exam scores than peers who did not use AI at all.

So to what extent can we rely on AI-generated output when we lack personal foundational broad overview in the related field? Yes, models can already outperform medical students on exams and multiple-choice licensing questions, sometimes by a large margin. But foundational knowledge can not be outsourced – current LLMs and other AI systems have all the data in the world but can not match them with a particular context relevant to the situation.

As for today, the evidence points to a conclusion that AI can be a very strong short-term performance amplifier while doing little for long-term understanding – unless it is embedded in a teaching design that forces learners to retrieve, explain, and critique.

Where AI seems most applicable in medical education

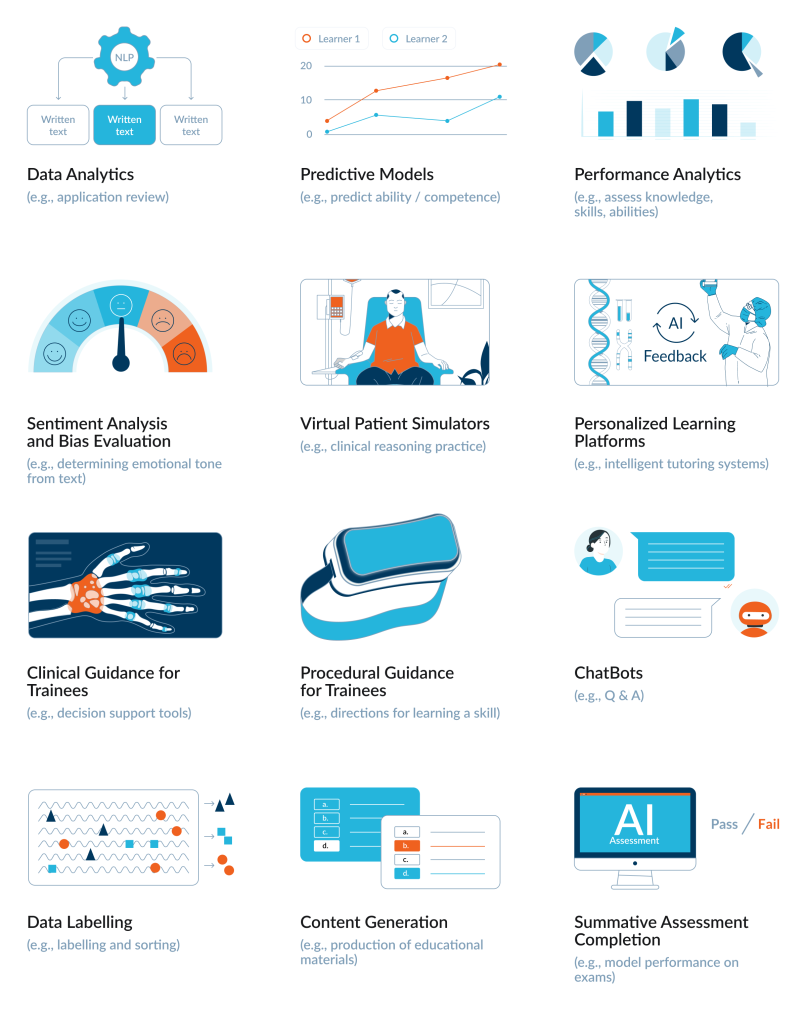

As you can see below, the review identified a specific spectrum of 191 articles and innovations categorized into distinct use cases. These applications range from administrative analytics to direct instructional support and performance testing.

Policies are arriving much slower than the tech

There is no global AI in medical education act, and most of the relevant documents live in the grey zone between ethics guidance and soft law. The World Medical Association’s 2025 statement on artificial and augmented intelligence in medical care frames AI explicitly as augmented intelligence: tools that support physicians’ judgement. It reiterates a physician-in-the-loop principle – a licensed doctor remains accountable for AI-mediated decisions and calls for education that enables clinicians to understand limitations, bias, and accountability of AI systems.

The WHO’s guidance on AI for health similarly emphasises that health worker education must include basic AI literacy, critical appraisal of algorithmic outputs, and awareness of bias and data protection obligations.

In Europe and other jurisdictions, AI used in education and vocational training is increasingly treated as high-risk under emerging AI regulation, which pushes universities toward impact assessments and monitoring but still leaves the details of teaching design largely to institutions.

Cheating in the age of co-writing

The pandemic already stretched the credibility of remote examinations. Remote exams become a team sport between a student and an autocomplete engine. Systems like GPT-4 routinely achieve or exceed the passing thresholds on USMLE and other high-stakes exams, often at or above the level of average medical students.This is good news for AI benchmarks papers and very bad news for the assumption that a multiple-choice test proves an individual’s competence.

When Lymar and colleagues surveyed learners at a Ukrainian medical university in late 2024, more than half admitted to some form of cheating on tests. Among those who used AI, the majority reported relatively “benign” uses, such as information search, but a substantial minority openly used it for academic dishonesty: ghost-writing essays (14%) or submitting entire assignments generated by AI (9%). Only about a third of respondents considered using AI in this way to be academic misconduct at all; the rest were either comfortable with it or undecided.

One aspect of the study particularly draws attention: some students described AI tools as an omnipresent helper that “can do any homework,” often copy-pasting the output not out of malicious intent but simply under time pressure and with a vague sense that “everyone does it.” This suggests that, for the new generation of students, LLMs are becoming as routine instruments as the Internet once became, yet educational research and policy are only beginning to disentangle where collaboration ends and cheating begins.

Co-pilots for postgradual education

After graduation and moving into clinical practice, today’s residents meet new tools for clinical decision support (CDSS), which help with continuous education, with summaries, test interpretation, and study planning. Trainee doctors expect AI to reduce workload but worry about erosion of clinical judgement. They often feel undertrained in how to question and contextualise the output.

CDSS were met with quite a lot of excitement, sometimes as a panacea, but quite soon after introduction, it became clear that designing CDSS as “any LLM, but trained on clinical data” is absolutely not enough.

In practice, CDSS should be integrated as a “second reader” that comes after physician’s own clinical reasoning: first the specialist take history, examine, form a differential and initial plan, and only then calls the system to check for blind spots, guideline updates etc., documenting where they agree or disagree and why. To avoid deskilling, training programs can deliberately design “CDSS-on / CDSS-off” moments – for example, asking residents to manage parts of a case without the tool and then use the CDSS as feedback, or to explain during rounds why the CDSS suggestion is appropriate or not in this specific patient.

Supervisors should review whether the “CDSS answer” was followed, as well as the quality of the resident’s independent reasoning and how they handled disagreements with the system. When CDSS use is embedded into case discussions and simulation training, it tends to strengthen calibration and pattern recognition. Evidence from CDSS and automation-bias research suggests that this kind of “reason-first, tool-second” workflow, plus explicit training on when to override the system, is what preserves skills while still gaining safety and consistency benefits.

Maybe even a new type of profession will soon emerge – educators who monitor what cognitive moves this tool encourages, which ones disappear, and how learners see the rationale behind a recommendation. Case logs and override data can become an assessment resource, highlighting where teams routinely disagree with the algorithm and where mistakes cluster.

For now, the common view is that CDSS should do what good clinical supervisors do: expose reasoning, welcome challenges, and leave trainees a little more capable after each decision.

Beyond the honeymoon phase

AI can compress the distance between novices and experts on certain exam metrics, especially in domains where pattern recognition in text or images is enough to score points. It can individualize feedback, simulate rare cases at scale, and give every student access to something that looks like a 24/7 personal tutor. It can help exhausted interns draft consult notes or research abstracts in between night shifts. It can sit the online quiz for them as well.

What it cannot do – at least not safely – is carry the moral and epistemic weight that medical education has traditionally tried to build into a doctor’s mind. As for today, the responsibility in medicine is not something that can be outsourced to a model – there is not even a remote understanding of how it can be achieved.

We have officially exited the phase of AI adoption, characterized by uncritical fascination, and entered a necessary phase of friction and adaptation.