Precision medicine in 2025 promises revolutionary healthcare personalization through genomics, AI-driven pharmacogenomics, and CRISPR gene therapies, but faces scalability hurdles – is it a “nice-to-have” or structural game-changer? We discuss the $119B precision medicine market, barriers in delivery, economics, and manufacturing, plus enablers like multi-omics, wearables, and cloud platforms.

What is precision medicine

It is a medical approach that seeks to personalize healthcare by taking into account a person’s unique characteristics at molecular, physiological, ecological, and behavioral levels. The concept has long recognized human uniqueness, yet it lacked practical methods. Early adopters appeared in alternative medicine but offered limited clinical evidence.

The idea of personalized medicine became operational in 2003 with validated DNA sequencing – a method to decode the genome base by base. The Human Genome Project mapped over 90% of the human genome. This effort took 13 years and cost about $3 billion but established the foundation for genomic analysis.

Today sequencing has become much cheaper: whole‑genome sequencing typically lands in the roughly $1,000–5,000 range per patient, while targeted oncology panels are often closer to $500–2,000. In the US and many European markets, these tests can be purchased directly, without a prescription, and customers receive the raw data files as part of the service. The datasets are huge – often ~100 GB per genome, but it’s a lifelong asset, which can be shared with clinicians or specialized genomics teams when it becomes relevant.

By late 2025, precision medicine commands a market exceeding $119 billion, with forecasts nearing $537 billion by 2035 at 16% annual growth, driven by genomics and oncology applications.

The progress is significant and measurable, yet it is too early to state that personalized medicine has fundamentally restructured healthcare delivery, it remains confined to narrow therapeutic niches and isolated departments.

Personalized CRISPR Therapy

Practical applications of personalized medicine are still scarce – we can collect enormous amounts of health data, but still have difficulties figuring out how to tailor treatment plans accordingly.

One of the possible practical applications – is gene therapy, which is still in its infancy as a method, however in certain cases its effect is so life-changing, that it feels like magic.

Diagnosis: KJ Muldoon is a toddler from Pennsylvania who was born on August 1, 2024, he appeared healthy at birth but began to deteriorate within days – became lethargic, refused food, and exhibited stiffness and seizures. He was rushed to the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, where doctors identified alarmingly high levels of ammonia in his blood – a toxic byproduct his body could not break down.

Genetic sequencing diagnosed a rare condition – severe urea cycle disorder affecting approximately 1 in 1.3 million births – Carbamoyl Phosphate Synthetase 1 (CPS1) deficiency. The condition prevents the liver from processing nitrogen, leading to ammonia accumulation that causes permanent brain damage or death. About 50% of infants with CPS1 deficiency do not survive their first year, and survivors typically require a liver transplant. In KJs case the problem was caused by a tiny mutation in his CPS1 genes.

The Treatment: With no off-the-shelf treatment available, a team led by Dr. Rebecca Ahrens-Nicklas and Dr. Kiran Musunuru proposed a radical solution: creating a custom gene-editing CRISPR-derived therapy from scratch for KJ. The task was to swap the problematic base pair in one of the gene copies.

CRISPR – is a gene-editing technology adapted from a bacterial immune system that uses guide RNA and Cas enzymes to precisely cut and modify DNA at targeted locations.

The team designed and manufactured the therapy in six months. It was delivered via lipid nanoparticles directly to liver cells – at approximately 7 months old, KJ received the experimental infusions.

Outcome and Journey: The therapy was a success. KJ’s body began producing the missing enzyme, and his ammonia levels stabilized, allowing him to process protein for the first time.

He was discharged home in June 2025 after spending 307 days of his life in the hospital. A moment celebrated by the hundreds of staff members who lined the hallways to cheer him out.

As of late 2025, KJ is thriving at home, requiring less restrictive dietary management and showing normal neurological development for his age.

There are about 30 million people in the U.S. are affected by rare diseases – could all now be cured with the same technique? Actually, no.

Barriers for gene therapy

KJ has a mutation in one gene, and at a single point of that gene – just one mistake in the DNA. This made him a suitable candidate for the experimental treatment – only one base of DNA had to be rewritten. While the human genome consists of approximately 3 billion base pairs, genetic diseases arise from thousands of distinct mutations across genes. Each case demands rapid, patient-specific design, manufacturing, and FDA authorization under a single-patient expanded-access. Making such an approach to personalized therapies unscalable, at least today.

The KJ miracle is currently an outlier. The editing toolbox is mature enough for first-in-class clinical wins, but too many aspects remain limiting – delivery, safety predictability, and scalable manufacturing.

There are plenty of reasons for that, and this list of reasons is not exhaustive.

Delivery: in vivo vs. ex vivo

The reason KJ’s treatment felt like magic is that it was delivered in vivo – injected directly into his body to edit cells inside his liver. This is the “holy grail” of in vivo gene editing, but it is exceptionally difficult to do safely for most organs.

The current market leaders, Vertex Pharmaceuticals and CRISPR Therapeutics, achieved their landmark commercial success with Casgevy (approved late 2023 for sickle cell disease), but it uses an ex vivo approach. This means extracting a patient’s stem cells, shipping them to a lab, editing, and re-infusing afterwards. This process requires the patient to undergo chemotherapy to wipe out their old bone marrow – weeks of inpatient care plus prolonged follow-up that limits treatment to only the most robust patients at specialized academic centers.

Companies like Intellia Therapeutics and Regeneron are chasing the in vivo dream (similar to KJ’s therapy) with candidates like NTLA-2001 for ATTR amyloidosis, which are currently in advanced Phase 3 trials but the trial is temporarily paused in October 2025.

Until in vivo delivery becomes the standard for more than just liver targets, widespread adoption will remain stalled by logistical complexity.

The N=1 economic problem

Pharma business models are built on “blockbusters” – drugs sold to millions. Rare diseases, by definition, have tiny markets and difficult customization – testing, regulatory file, etc. KJ’s condition affects 1 in 1.3 million. There is no traditional ROI model for developing a multi-million-dollar drug for ten people.

Bluebird Bio, a pioneer in the space, has struggled financially despite having approved therapies (like Lyfgenia), because of slow uptake, safety warnings, and the high fixed costs of commercialization.

For ultra-rare cases like KJ’s, the cost of manufacturing a custom-grade viral vector or lipid nanoparticle batch is prohibitively high. We are seeing the rise of non-profit and academic consortiums, but they lack the capital of big pharma.

Scalability

Manufacturing gene therapies is currently closer to artisanal craftsmanship than industrial assembly.

Beam Therapeutics is working on “base editing” – a more precise version of CRISPR that swaps single letters, similar to what KJ needed to reduce off-target risks, but manufacturing these complex editors at scale is a massive engineering hurdle.

Verve Therapeutics (co-founded by Dr. Musunuru, who treated KJ) is attempting to break the “rare disease only” mold by targeting high cholesterol – a mass-market condition. If they succeed, it would prove that gene editing can scale to millions, but they face an incredibly high bar for safety from regulators, as they are treating otherwise healthy-feeling people.

But aspirations are high – on September 25, 2025 The Department of Health and Human Services launched a national program, aiming to make personalized and affordable cures available to all rare disease patients.

What other technologies make personalized medicine possible today?

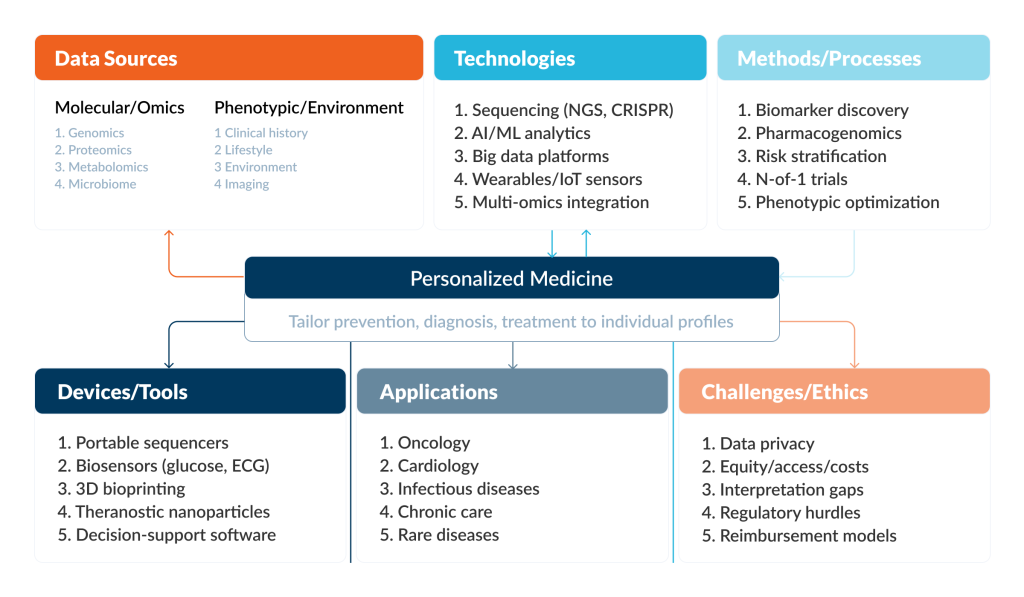

Technological infrastructure supporting personalized medicine today encompasses far more than genomics. It represents the whole ecosystem of data generation, AI, cloud infrastructure, and clinical decision support systems that are deployed across clinical settings.

Let’s explore enabling technologies available today.

Personalized medicine is a concept that spans across all specialties – from cardiology to sports medicine, which makes its influence really significant, but introduction is tricky, as it demands such complex infrastructural changes that it is impossible to grasp by a single person’s mind.

DNA Sequencing

How it works: Modern sequencing generates billions of DNA sequence reads in parallel, allowing comprehensive interrogation of the genome in a single run. Processing time has compressed dramatically – clinical laboratories can deliver results within 4 days for critical pediatric cases.

What problem it solves: patients with rare genetic diseases often undergo years of specialist evaluations without a molecular diagnosis; under standard clinical care a substantial fraction may remain undiagnosed. Sequencing can identify pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants that explain disease and can also detect variants relevant to drug response.

In oncology, tumor sequencing is used to identify genomic alterations with potential therapeutic relevance, supporting targeted therapy selection and companion diagnostic strategies.

In pharmacogenomics, sequencing reads a person’s drug-relevant genes to identify variants that predict how they metabolize or react to specific medicines, this helps to choose a drug or dose and avoid toxicity.

AI and Machine Learning Analytics

How it works: AI and machine learning (ML) algorithms, particularly deep learning and neural networks (such as “DrugCell”), process vast, heterogeneous datasets that are too complex for traditional statistics. These models “learn” intricate features and dependencies within genomic data, electronic health records (EHR), and medical imaging to predict outcomes.

What problem it solves: the “data deluge” problem – by navigating the immense complexity of multi-modal data to find actionable patterns. AI drastically reduces the trial-and-error nature of prescribing by accurately predicting drug responses and identifying novel regulatory markers that human analysis would miss.

AI excels by: (1) predicting drug response before clinical trials, reducing development risk; (2) achieve diagnostic accuracy that rivals or exceeds specialist clinicians; (3) allows creating unified risk models by integrating genomics, imaging and clinical notes into; (4) enabling real-time clinical decision support at point-of-care.

Big Data Platforms and Cloud Infrastructure

How it works: These platforms utilize cloud-native infrastructure to integrate and manage zettabytes of heterogeneous data, merging clinical EHRs with “omics” data and real-time streams from wearables. Advanced platforms now often employ decentralized approaches, such as blockchain, to allow secure, patient-controlled data sharing.

What problem it solves: personalized medicine needs very large cohorts and multimodal data to find clinically useful patterns, but traditional “download-to-local” analysis becomes slow, expensive, duplicative, and hard to secure. Cloud trusted research environment models reduce data movement, centralize access control/auditing, and enable collaboration and scaling without copying sensitive datasets across institutions.

Multi-Omics Integration

How it works: This approach combines data from different molecular layers – genomics (DNA), transcriptomics (RNA), proteomics (proteins), and metabolomics (metabolites), to create a comprehensive digital twin of a patient’s biology. It often employs spatial analysis to understand how these molecules interact within the tissue architecture.

What problem it solves: it helps explain why patients with the same genetic mutation might respond differently to treatment by revealing the downstream effects on proteins and metabolism.

Wearables / IoT Sensors

How it works: they provide continuous, real-time monitoring of physiological and biochemical parameters, e.g., heart rate, glucose, hydration etc. These devices have moved beyond simple fitness tracking to medical devices, integrated directly into clothing or patches.

What problem it solves: by capturing data in the patient’s daily environment, they provide a more accurate picture of health than sporadic clinic-based measurements.