Modern medical practice is virtually unthinkable without numerous wearable electronic devices. Miniature flexible devices that continuously monitor blood glucose levels, blood pressure, pulse, or other vital parameters have become an integral part of daily life and an indispensable element of diagnostics and treatment.

The widespread adoption of such devices has created a new problem — growth in electronic waste. Many wearable medical electronics are designed for short-term use and require disposal after weeks or even days. This not only generates increasing volumes of toxic e-waste but also leads to substantial growth in greenhouse gas emissions. A new study published in Nature provides the first detailed analysis of how e-waste and greenhouse gas emissions from these devices are likely to grow and identifies the most effective mitigation strategies.

Global electronic waste is rising rapidly: in 2010, 34 million tons of broken and obsolete electronics were landfilled worldwide, rising by 82% to 62 million tons by 2022. By 2030, according to the Global E-waste Monitor, annual e-waste generation will reach 82 million tons.

Yet less than a quarter of this volume enters recycling streams (8 million tons in 2010 and 13.8 million tons in 2022). Although recycling volumes are increasing, waste generation is growing nearly five times faster than recycling capacity.

Wearable medical devices are expected to represent an increasingly significant share of this total. By 2050, production of medical monitoring devices is projected to grow 42-fold, reaching 2 billion units annually.

These devices also pose particularly difficult recycling challenges: they are extremely compact, typically not designed for disassembly or repair, and often contain components glued together that cannot be separated without damage. This creates fire risks when attempting to remove lithium-ion batteries during dismantling.

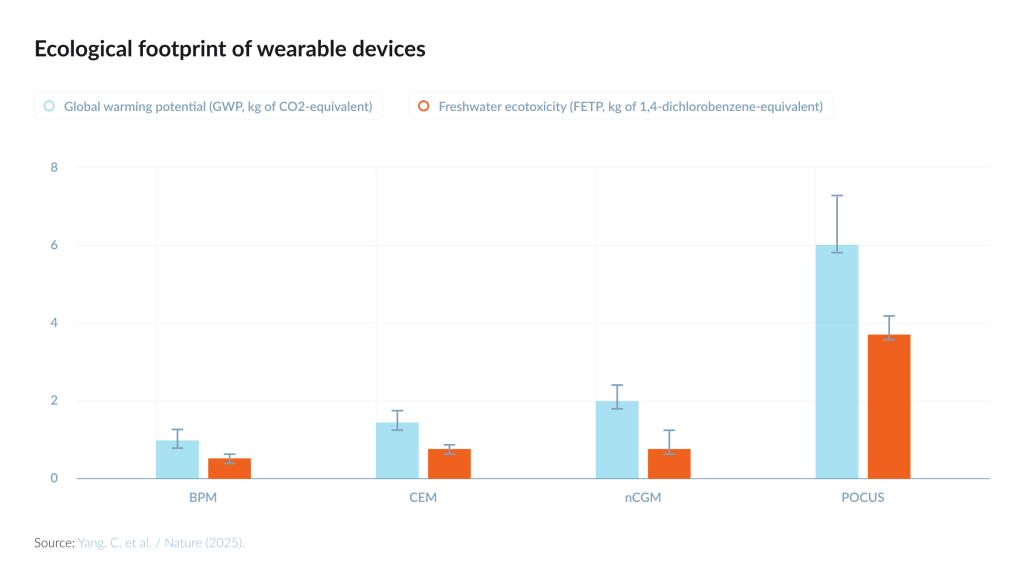

Global warming potential (GWP, kg of CO2-equivalent) and freshwater ecotoxicity (FETP, kg of 1,4-dichlorobenzene-equivalent) for the four wearables. Source: Yang, C. et al. / Nature (2025).

Recycling is often economically unviable: the value of materials such as gold, copper, and rare earth elements recoverable from wearable devices does not justify the costs of disassembly, sorting, and chemical processing. But recycling addresses only part of the problem. Manufacturing vast quantities of essentially disposable electronics generates substantial CO₂ emissions and consumes many other resources.

Bozhi Tian from the University of Chicago and Fengqi You from Cornell University, together with colleagues, set out to analyze the full cradle-to-grave life cycle of several representative devices in order to identify environmental “hotspots,” determine where the greatest greenhouse gas emissions and pollution arise, forecast how these parameters may evolve in the future, and evaluate which technological changes could minimize their impact.

For their analysis, the researchers selected four device types: non-invasive continuous glucose monitors (nCGM), continuous ECG monitors (CEM), blood pressure monitors (BPM), and point-of-care ultrasound patches (POCUS) — a set that includes both established commercial products (BPM and CEM) and emerging technologies such as ultrasound patches and next-generation glucose monitors.

The team quantified the environmental footprint of each component and its packaging. In addition to carbon emissions, they examined water use, soil and human toxicity, freshwater ecotoxicity, and other indicators.

The carbon footprint over the full life cycle of these devices ranged from 1.06 kg of CO₂-equivalent for a BPM to 6.11 kg for a POCUS system. For comparison, 6 kg of CO₂-equivalent corresponds roughly to a 15–20 km car journey. Among all components, printed circuit boards accounted for the largest share.

“More than 70% of the carbon footprint of a device comes from the circuit boards,” said Tian.

According to the researchers’ projections, by 2050 annual demand could reach approximately 1.4 billion nCGM units, 0.4 billion CEM units, 0.2 billion BPM units, and 11.4 million POCUS systems — about 42 times higher than in 2024. Under a moderate growth scenario, this volume would generate 3.4 million tons of CO₂-equivalent emissions each year, rising to 10.4 million tons under an aggressive scenario. Discarded devices of these four types would meanwhile produce between 0.1 and 1.3 million tons of electronic waste annually.

Modeling showed that measures such as replacing plastic casings with biodegradable alternatives have only marginal effects, cutting the footprint by just 2–2.6%. Even a hypothetical 100% recycling rate for plastics would reduce emissions by no more than 6–7%.

Substituting metals offers a far greater reduction in carbon footprint. Replacing gold with silver, copper, or aluminum cuts emissions by about 30%, reflecting the high carbon intensity of gold mining. Toxicity indicators also fall by roughly 60%.

However, the most powerful ecological strategy is extending the lifespan of electronic components — the “computers” inside wearable devices. If circuit boards could be used at least three times longer, the carbon footprint of each monitoring cycle would drop by around 60%.

“Our work offers a systems-engineering framework for many transformative technologies, from wearables to AI and robotics, so that technical innovation and environmental stewardship can advance together,” said co-author Chuanwang Yang of the University of Chicago.