As recently as yesterday, 32 GB of RAM for a PC was a routine purchase; today it looks like a full-fledged investment appreciating faster than gold and certainly faster than bitcoin. What is increasingly resembles a brewing crisis: the race to ramp up AI capacity is often coming at the expense of other sectors, and manufacturers whose products have had the good fortune to become coveted in this race are quick to reshuffle priorities, with little concern for the consequences for ordinary users.

In Tokyo’s Akihabara district, popular 32-gigabyte DDR5 kits have, in the space of a few weeks, jumped from about 17,000 yen in mid-October to more than 47,000 yen in December – an increase of almost 180%. 128-gigabyte kits there have more than doubled in price over the same period.

In Germany, DDR5 prices have risen by roughly 50% in recent weeks, and 16 GB of DDR5 now starts at a minimum of €150, with dual-channel kits suitable for a standard build often selling for significantly more. The price surge is spilling over into manufacturers of pre-built systems as well: UK-based CyberPowerPC has announced price increases, including in the British market, explicitly linking them to the sharp rise in RAM and SSD costs and expecting this pressure to persist into 2026.

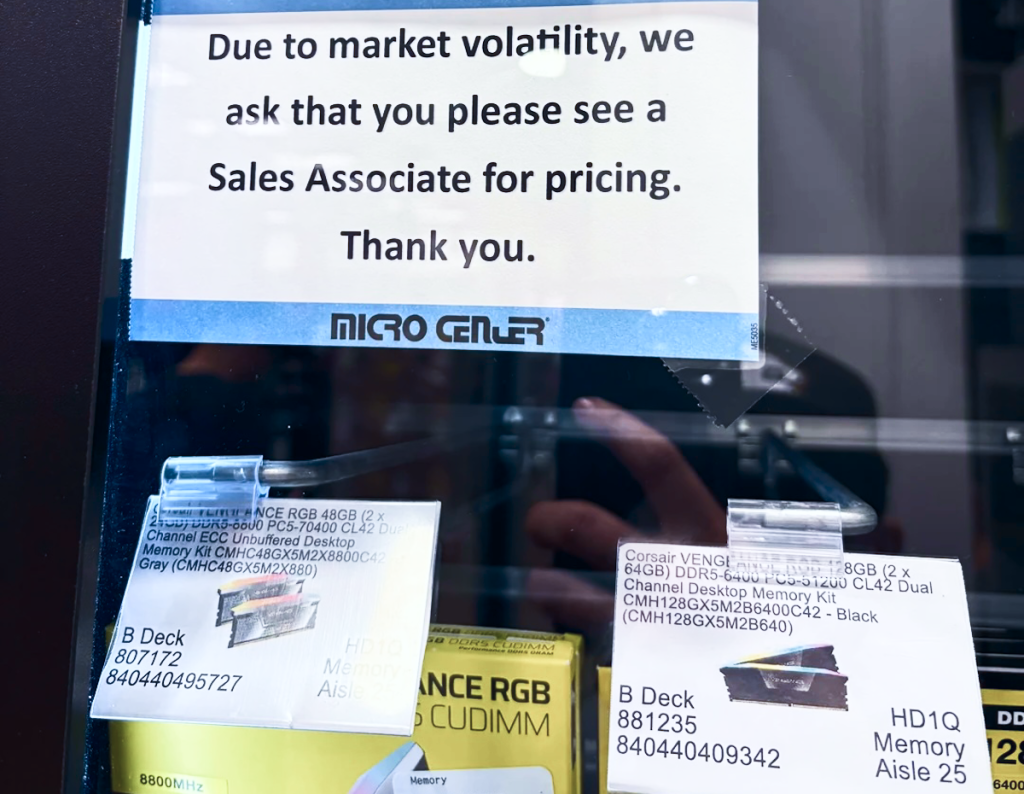

In the United States, retailers are likewise adapting to scarcity: stores are limiting the amount of DDR5 that can be sold to a single customer and increasingly refrain from listing fixed prices for memory, instead advising customers to check prices at the counter – they are rising too fast to keep up.

Against the backdrop of these “Hunger Games”, remarkable stories have begun circulating online, alleging that OpenAI employees are buying up DDR5 in retail stores.

How reliable this information is is hard to say. But this grotesque picture fits all too well into the broader context of what is happening in the world.

So what is going on?

AI has become a “memory vacuum cleaner”

The main reason for the price spike now sounds almost routine: the boom in artificial intelligence is being blamed for everything. Building AI infrastructure is literally “eating up” chip volumes faster than the industry can produce them. Memory is needed not only for “regular” server DDR5, but also for high-bandwidth HBM, which is paired with top-tier AI accelerators. Production lines and silicon wafers are being reallocated to where margins and hype are higher, which means there is less standard DRAM left for PCs and consumer electronics.

The scale of this acceleration is indirectly reflected in the dynamics of the spot market: according to TrendForce, since the beginning of September, spot prices for DDR5 chips have risen by more than a factor of three. And at the level of complete systems, the effect is already being described as extreme: CyberPowerPC told that since 1 October 2025 its procurement prices for RAM have surged by up to 500%, forcing the company to raise prices on its builds in the US and the UK.

Will competition shrink?

The problem is that about 93% of the global DRAM market is controlled by just three companies: Samsung, SK Hynix, and Micron. Their production priorities are shifting toward server and AI customers: if you are not a server client, you are relegated to “second-tier” status.

And sometimes not just “second-tier”. In early December, Micron announced its decision to wind down its consumer brand Crucial. According to the company, consumer memory products manufactured by Micron will continue to ship until February 2026 with warranty support preserved, after which Micron will “exit the Crucial consumer business, including the sale of Crucial consumer products across major retail, e-tail and distribution partners worldwide.”

In its press release and market comments, Micron explicitly links this decision to the explosive growth of data centers and promises improved supply for “larger strategic customers in fast-growing segments.” In effect, AI-driven contracts are crowding out the interests of the mass consumer.

This now leaves only two companies competing for the consumer market. It is obvious that this may also affect price levels, including in the medium term. And many are unhappy about that. The popular YouTube channel Gamers Nexus points out that in the US, government investments and tax incentives are flowing to companies that then increase market concentration and pivot toward B2B giants.

Who will be hit?

It is obvious that the growing shortage will affect far more than the desktop PC market. It will feed into the prices of laptops, phones, networking equipment, and industrial hardware. There are so many areas where price increases are likely that it is hard to list them all.

For example, the impact has already reached the game console market, where demand is about to spike ahead of the Christmas holidays. The PlayStation 5 and Xbox Series both use 16 GB of GDDR6 – the same class of graphics memory found in GPUs. That is why the console market does not exist in a vacuum: when AI and data centers “vacuum up” memory output, prices rise for consoles as well. Digital Foundry notes that, after the price hikes already seen, there is every chance of further increases in 2026.

At the same time, there is insider but unconfirmed information that Sony pre-booked a large volume of GDDR6 when prices were lower, which may temporarily shield the PS5 from the worst shortage scenarios. But even if such a buffer exists, it is time-limited. Once the “cheap” batches are gone and the old contracts expire, console pricing will inevitably adjust to the new market reality.

What’s next: the 2026 window

The most realistic range of scenarios for 2026 looks like this: high prices will persist until either the AI build-out slows or manufacturers expand capacity more aggressively than they are doing now. But plants and production lines cannot be built in a single quarter, and memory is a market that has already suffered from unexpected gluts in the past, so companies may prefer to ramp up cautiously.

Three forces could cool the market: partial saturation of mega-scale AI projects and a shift to more moderate purchasing; faster commissioning of new capacity and normalization of inventories; and a turn in demand toward cheaper device configurations, with end-device manufacturers economizing on memory.

And two factors could drive it even hotter: new large-scale “take everything you can produce” contracts and a further shift in priorities toward HBM and enterprise supply.

In essence, this is a clash between two economies: the home-upgrade economy and industrial AI. As long as the latter is willing to pay more and faster, the former will feel it in the wallet – from building a PC to the price of the next laptop or smartphone.