Artificial intelligence is beginning to outperform humans in narrow but economically consequential tasks, raising anxieties about job security and even agency. We are seriously discussing the possibility of losing control over AI. And one of the proposed ways of dealing with it is integration: linking the nervous system to digital tools through the brain-computer interfaces (BCIs).

The idea of human-computer symbiosis can be traced back to the 1960s, but today, it finally feels operational. Laboratory demonstrations have shown that implanted BCIs have enabled some people with paralysis to control robotic arms. In parallel, high-profile founders are pushing the topic into the spotlight, often with rhetoric that slips from therapy into augmentation. So maybe the next evolutionary step in human capability will be made by our choice, not by random forces.

To test those claims against current science, we spoke with Peter Meijer, PhD, a data scientist, algorithm designer, image-processing specialist, and the developer of “The vOICe” – a sensory substitution technology that enables blind people to perceive live camera views through sound.

What we found out is that an augmented human brain is still in the department of science fiction.

There is no single official definition of what constitutes a BCI beyond those used by specific interest groups. One of several working definitions of a BCI comes from the BCI Society: a system that measures brain activity and converts it in (nearly) real-time into functionally useful outputs to replace, restore, enhance, supplement, and/or improve the natural outputs of the brain, thereby changing the ongoing interactions between the brain and its external or internal environments. It may additionally modify brain activity using targeted delivery of stimuli to create functionally useful inputs to the brain.

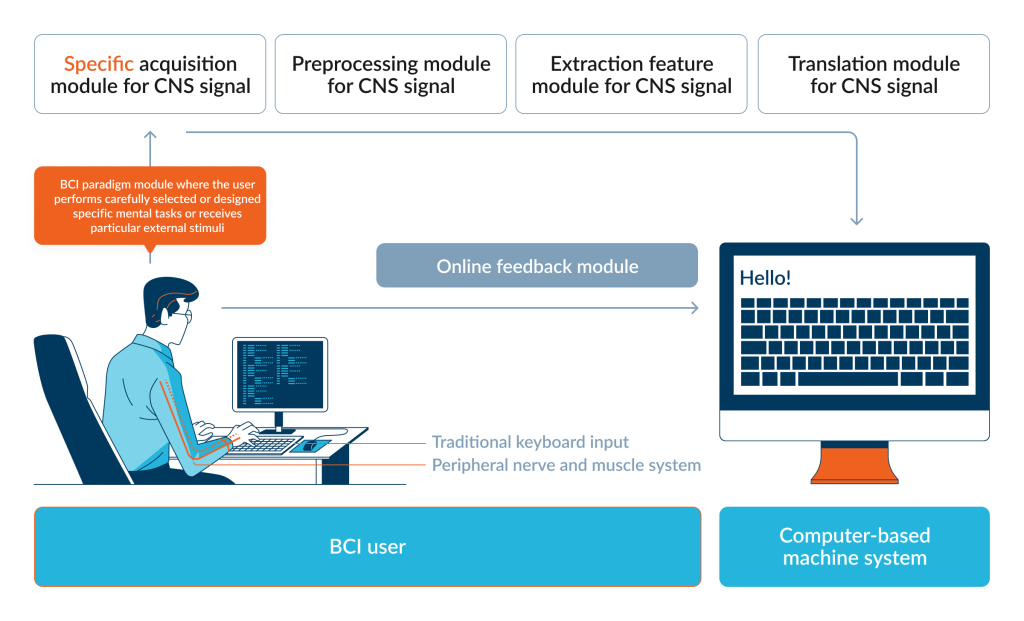

For a BCI to function we need:

– Brain activity;

– BCI paradigms;

– BCI neural encoding and/or decoding;

– Measurement and/or stimulation techniques;

– Computer-based machine systems;

– Feedback loop.

2Digital: In 2026, what qualifies as a BCI?

Peter Meijer: It’s not a protected term. Everybody basically uses the term that they see as appropriate or that fits the bill for commercial PR. But I disagree with the definition you provided because it is too restrictive; it requires that there is a readout of brain signals – you have to measure them.

However, if you take that definition, then you immediately exclude visual prostheses like the Dobelle brain implant or the Orion Visual Cortical Prosthesis because these are devices that purely give input from the outer world, they don’t measure brain signals. And if you think about cochlear implants, then you find different interpretations: some will say it’s a BCI, and others will say that no, it interfaces with the auditory nerve, which then communicates with the brain. Then deep brain stimulation may be considered a BCI, even though there’s usually no information transfer; it’s just stimulating a part of the brain in order to relieve symptoms of, for instance, Parkinson’s.

The future is that visual prostheses will be bidirectional because if you can measure the neural response to a certain stimulus, then it’s probably easier to optimize the results that you finally get. But in the broader scope of things, I think that people will also consider input-only brain implants for restoring vision, like the ones that I mentioned, to be BCI devices. It can shift over time.

2Digital: Then why do we need such strict definitions?

Peter Meijer: Sometimes it’s a matter of company politics. If you are, as a company, working on brain implants for restoring vision, you have to tell your investors what you’re working on and who your competitors are. And it’s convenient if you can exclude, for instance, sensory substitution because it doesn’t directly interface with the visual cortex. You just don’t mention it to the investors. And then it is only, say, those two competitors with invasive implants. That’s very convenient. So there is politics also involved in what is considered a BCI and what is not.

2Digital: Which BCI categories are deployable outside research labs?

Peter Meijer: There’s a broad range of devices, so there’s not one single answer. You have, of course, the EEG headsets – sometimes consumer devices, and sometimes for clinical use, like NeuroSky and Emotiv. Basically, you put electrodes on your scalp to measure brain signals,and the changes in signal as you focus, for example, on multiple flashing items on a screen, can be used to know whatyou are looking at. It’s rather widely available, though I don’t know how many people use this or how many devices have been sold.

Then there is the Neuropace implant used by people with epilepsy: it measures brain waves, and if it sees abnormal behavior, it applies pulses that remove this strange behavior and hopefully prevents a seizure. From what I know, there are several thousand people walking around with that type of implant.

There’s also ONWARD, a company doing spinal stimulation, but they’re still investigational devices – not generally approved as a commercial product.

I already mentioned cochlear implants – these are widely used and commercially available – but then the list ends. A lot of what you hear about now, like what Neuralink, Paradromics, and Cortigent are doing, are investigational devices: in clinical studies, they can be applied at a small scale, but they’re not generally approved by the FDA, and they didn’t get a CE mark for Europe either. So in a nutshell, it’s a very scattered set of things depending on the device and the application.

2Digital: But wait, in public discussion, we are talking about different devices that help blind people see – Blindsight, for example.

Peter Meijer: It’s true: you get these initial reports – that are widely distributed in the media – of a blind person who hadn’t seen for years suddenly seeing flashes of light. It’s wonderful.

A retinal implant – Argus II – was approved by the FDA to be commercially sold, and over 300 people received that particular implant, but the functional benefit was extremely limited.

And if you’re a scientist, then you look at things differently. You look at what works: what can it do, what kind of benefit does it offer to the patient? After weeks or months, the honeymoon effect wears off, and then they ask themselves: what can I really do with this device that I could not do before, or that I cannot do through other means like a long cane, an app on my mobile phone, or echolocation?

And then, it turns out that this Argus II retinal implant offers very, very little. You get very blurry blobs of light and that’s it. People trained with it a lot, but it did not improve.

There was an open contest in 2018 about blind navigation and object identification, where two people with an Argus II retinal implant and one blind user with The vOICe sensory substitution glasses (a person guided by sound signals) participated. That contest was won by the person with The vOICe by a large margin. In that case, The vOICe Android app ran on Chinese glasses that only cost $200, without any surgical intervention, while the Argus II retinal implant cost something like $150,000 a piece.

These are among the very rare cases where there was an actual benchmark between different technologies.

2Digital: In vision restoration, what is the trade-off between invasive implants and sensory substitution, if there is one at all?

Peter Meijer: One trade-off is that with an invasive implant, you get visual sensations immediately. If you stimulate the visual cortex and you are late-blind (not early-blind), then you get a visual percept, so that’s very nice. And especially if you haven’t seen for a long time and you remember what vision was like, that’s really sensational – something sensory substitution does not give.

Does, after sufficient practice, the experience of sensory substitution become visual, truly visual? Opinions among blind people vary. There has been a late-blind user who insisted the experience was definitely visual, with light and all that, but for most users it’s sound, with a visual interpretation built on it. So that’s an advantage of brain implants: you get visual sensations.

Whether it’s functional is another matter. With a brain implant, you may get just blobs of light, but that is not particularly useful. And if you look at functional vision, then the little information we have from benchmarking indicates that sensory substitution works better.

2Digital: Your work is often described as a non-invasive vision BCI via sensory substitution. Can you elaborate on how the brain can learn a stable image-to-sound mapping?

Peter Meijer: The short answer is: we don’t know. There’s no precursor for how to learn this mapping, so you use a bit of intuition and a bit of common sense.

You start with simple exercises, like reaching and grasping for a bright object on a dark tabletop, which helps you learn to coordinate movements of your hands and arms with the soundscapes representing the visual input. After an hour, maybe two, you can often do this, and it’s rather rewarding because it’s something you cannot do when you’re fully blind and have to move all over the tabletop to find the object; now you can reach for it directly.

But when it goes beyond that – recognizing a chair as being a chair – it becomes excruciatingly hard. There are millions of chair designs, with different textures and colors; you can view a chair from many different viewpoints; shading and lighting vary, and yet they’re all chairs. Learning to recognize that without vision through soundscapes that contain visual information is extremely difficult, and we really don’t know yet how far it goes – how well people can learn this through extensive use.

The same, by the way, applies to brain implants for restoring vision. Daniel Palanker has recently made the valid criticism that thus far, no brain implant has demonstrated form vision – recognizing forms from how they show up as a phosphene map in the brain; the closest that has been shown is monkeys recognizing letters.

2Digital: What are the most common misconceptions about blindsight and telepathy claims with a BCI?

Peter Meijer: The main misconception is that people think that if your technology becomes advanced enough, the problem is solved. They do not take into account that it is unknown what types of signals the brain wants or needs for a certain function, and that especially applies to visual prostheses.

You can have the most advanced technology: fully biocompatible, with tens of thousands of electrodes. But if the brain doesn’t like the signals – if receptor fields are too wide, neural recovery time is too large, or neurons get accustomed and reduce responses – you get very poor overall results. There’s still very little known about what signals the brain needs to get anything like natural vision, so it’s not simply a matter of more advanced tech. And that’s what companies try to ignore: they just don’t know whether their device will work in practice.

And there is no evidence whatsoever for Elon Musk’s claim that initially it will be like “Atari graphics.” If it worked like Atari graphics, it would be a major breakthrough because thus far, there’s no indication whatsoever that the quality of vision from a brain implant in visual cortex will be anything like that, let alone that it would go up to normal vision and beyond.

That’s against what is known in science about vision and how the visual cortex responds to stimuli. Vision experts will tell you the receptive fields are too large: even with 10,000 electrodes you don’t get a 100-by-100 resolution. In practice, you get far less because receptive fields overlap.

And there’s also a safety misconception: you can’t stimulate 10,000 electrodes all at the same time like when looking at a blue sky. If you try to drive that many electrodes above the perceptual threshold simultaneously, the total current adds up to something dangerous – you’ll definitely get seizures, and it might even kill you.

2Digital: Do I understand correctly that, in BCI development for brain output, we need well-defined theories of which signals from the brain we want to use as we cannot just use any arbitrary impulse a person has? We can’t read any thoughts.

Peter Meijer: No, we cannot read internal thoughts, not yet at least. And not for a long time, I think.

It’s all peripheral. You can basically skip the neural pathways that control your muscles by directly reading from the motor cortex and mapping those complex signals into an intended movement – like moving a cursor to a certain position. But there’s nothing like reading thoughts. The closest is perhaps being able to read speech: the intention to speak is something that can be extracted from the motor cortex, and those are generally the kinds of outputs you want to share: you want to speak, it doesn’t work, and then, via this interface, you can speak.

In the longer run, yes, there is the possibility that you can read sentences from the brain that, upon second thought, you don’t want to speak because they’re inappropriate or whatever – and then it’s already decoded, and it would go out of your brain. There was an article not so long ago about a special code you have to think of to distinguish thoughts you want to communicate from thoughts you want to keep private. But the risk of reading thoughts is still very, very low at the individual level.

At the societal level, the risks are different. Even a simple BCI that reads brain signals might indicate whether you are tired, or whether your attention span is short or long, and in theory, you could adapt the ads you see on your screen – show them at the moment you’re most susceptible to buying something. It’s still theoretical, but it’s a little bit scary; through similar means, you might influence how people think about certain subjects, so it becomes political.

But it’s far out for now – still, theoretically possible.